Program Notes: Mozart Requiem

Notes about:

Mozart’s Requiem, K. 626

Price’s Symphony No. 3 in C minor

Program Notes for MAy 12 & 13, 2023

Mozart Requiem

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Requiem, K. 626 (completed by Robert Levin)

Composer: born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria; died December 5, 1791, Vienna

Work composed: 1791. Mozart died before completing the Requiem, an anonymous commission from Count Franz Walsegg von Stuppach. The Requiem was originally finished by one of Mozart’s students, Franz Xaver Süssmayr. The version heard in these concerts was realized and completed by musicologist Robert Levin in 1991.

World premiere: Helmuth Rilling conducted the first performance of Levin’s realization in August 1991 at the European Music Festival in Stuttgart.

Instrumentation: soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists, SATB chorus, 2 bassoons, 2 basset horns (or clarinets), 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, organ, and strings

Estimated duration: 53 minutes

The mysterious circumstances surrounding Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem have lent the work an aura of romance and intrigue almost as compelling as the music itself. In the summer of 1791, Count Franz Walsegg von Stuppach sent a messenger to Mozart with an anonymous commission for a Requiem intended to honor Walsegg’s late wife. Walsegg, an amateur musician, had a habit of commissioning works from well-known composers and then claiming them as his own, hence his need for anonymity and subterfuge. Chronically hard up, Mozart accepted the commission. He completed several sketches before putting the Requiem aside to finish Die Zauberflöte and La Clemenza di Tito and to oversee a production of Don Giovanni.

In October 1791, in failing health, Mozart returned to the Requiem. When Mozart died two months later, the Requiem remained unfinished. Mozart’s wife, Constanze, facing a mountain of debt, asked one of Mozart’s associates, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, to complete it. Süssmayr agreed, but his claims of authorship of the later movements of the Requiem have provoked sharp debates over which man wrote what, debates that continue today.

In 1991, musicologist Robert Levin presented his ‘completed’ version of the Requiem in which he corrected what he called Süssmayr’s “errors in musical grammar.” This version has become preferred by conductors and ensembles; since its premiere, there have been over 125 recordings of Levin’s edition.

The fine attention to detail in the meaning of the words of the requiem mass dictates the musical structure throughout. The chorus’ heartfelt pleading in the opening lines, “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine” (Grant them eternal rest, O God), are presented in a dark minor key. This is transformed into a promise of glowing eternity in the next sentence, “Et lux perpetua luceat eis” (and may perpetual light shine upon them) as the music moves into the light of a major key. The strong Kyrie (Lord, have mercy/Christ, have mercy) that follows is set in a stark fugue, Mozart’s homage to J. S. Bach.

The Sequence, which is composed of a number of short movements, begins with the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), whose fiery, agitated setting and orchestral accompaniment bring the terror and fury of the text frighteningly alive. In the Tuba mirum, the bass soloist and a solo trombone proclaim the Day of Judgment, followed by each of the soloists in turn. The chorus returns to beg for salvation from hell in the powerful Rex tremendae, which is followed by the more intimate pleading of the Recordare, in which each of the soloists makes a personal petition to God. The gentleness of this movement is followed by the thunder of the Confutatis, which juxtaposes the images of the damned consigned to the flames of hell with that of the supplicant kneeling in prayer. Then comes the exquisite Lacrymosa, in which the chorus grieves and sobs; The sighing appoggiaturas of the violins echo the lamenting of the text. In the Offertory, the chorus ends its plea for mercy with a reminder of God’s promise to Abraham; these words are set into a tremendous fugue, which recurs at the end of the graceful Hostias.

With the Sanctus comes the first wholly joyful expression of emotion, as the chorus and orchestra together sing God’s praises with shining exclamations in the brasses and a fugue on the words “Hosanna in the highest.” The operatic grace of the melody of the Benedictus, sung by the four soloists, conveys the sense of blessedness of those “who come in the name of the Lord;” this is followed by a recurrence of the choral fugue from the Sanctus. With the Agnus Dei, the chorus and orchestra return to the darkly shifting mood of the opening movement; this culminates in the Communio, which uses the music of the opening Requiem aeternam and concludes with the same fugue used in the Kyrie, but this time on the words “cum sanctis tuis in aeternam” (with Thy saints forever).

Florence price

Symphony No. 3 in C minor

Composer: born April 9, 1887, Little Rock, AR; died June 3, 1953, Chicago

Work composed: 1938-39

World premiere: Valter Poole led the Michigan WPA Symphony Orchestra (aka the Detroit Civic Symphony) on November 6, 1940

Instrumentation: 4 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, castanets, crash cymbals, gong, orchestral bells, sand paper, slapstick, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle, wood block, xylophone, celesta, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 28 minutes

Florence Price, the first Black female American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra, enjoyed considerable renown during her lifetime. Her compositional skill and fame notwithstanding, however, the entrenched institutional racism and sexism of the white male classical music establishment effectively erased Price and her music from general awareness for decades after her death in 1953. More than 50 years later, in 2009, a large collection of scores and unpublished works by Price were discovered in a house in rural Illinois. Since then, many ensembles and individual musicians have begun including Price’s music in concerts, and audiences are discovering her distinctive, polished body of work for the first time.

The daughter of a musical mother, Price was a piano prodigy, giving her first recital at age four and publishing her first composition at 11. During her childhood and teens in Little Rock, Arkansas, Price’s mother was the guiding force behind her piano and composition studies. In 1903, at age 16, Price won admittance to New England Conservatory (she had to “pass” as Mexican and listed her hometown as Pueblo, Mexico, to circumvent prevailing racial bias against Blacks), where she double majored in organ performance and piano pedagogy. While at NEC, Price also studied composition with George Whitefield Chadwick. Chadwick was an early advocate for women composers, and he believed, as did Antonín Dvořák before him, that American composers should incorporate the rich traditions of American vernacular music into their own work, rather than trying to imitate European styles.

Price, already inclined in this direction, was encouraged by Chadwick; many of her works reflect the expressive, distinctive idioms of what were then referred to as “Negro” traditions: spirituals, ragtime, jazz, and folkdance rhythms whose origins trace back to Africa. In 1938, Price wrote, “We are even beginning to believe in the possibility of establishing a national musical idiom. We are waking up to the fact pregnant with possibilities that we already have a folk music in the Negro spirituals – music which is potent, poignant, compelling. It is simple heart music and therefore powerful. It runs the gamut of emotions.”

Price’s later works, including the Symphony No. 3, fuse these uniquely Black American musical idioms with the modernist European language employed by many classical composers of the day. Price explained, “[The Symphony No. 3 is] a cross section of present-day Negro life and thought with its heritage of that which is past, paralleled or influenced by concepts of the present day,” specifically, her use of the expressively dissonant harmonic language of the 20th century.

Each of the Third Symphony’s four movements juxtaposes elements of both musical traditions, often in opposition to one another. The Andante; Allegro opens with a slow, pensive introduction in which brasses and winds feature prominently. This gives way to the Allegro’s restless, harmonically unsettled first theme. A solo trombone introduces a contrasting second section, featuring original melodies grounded in the Black vernacular tradition. The pastoral quality of the Andante ma non troppo evokes the warm serenity of a summer afternoon, while the Juba, an African dance brought to America by enslaved people, transmits its infectious ebullience through syncopated rhythms and specific percussion accents, particularly the castanets and xylophone. The closing Scherzo combines Black-inflected rhythms and 20th-century harmonies in an orchestral showcase full of virtuosic passages.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

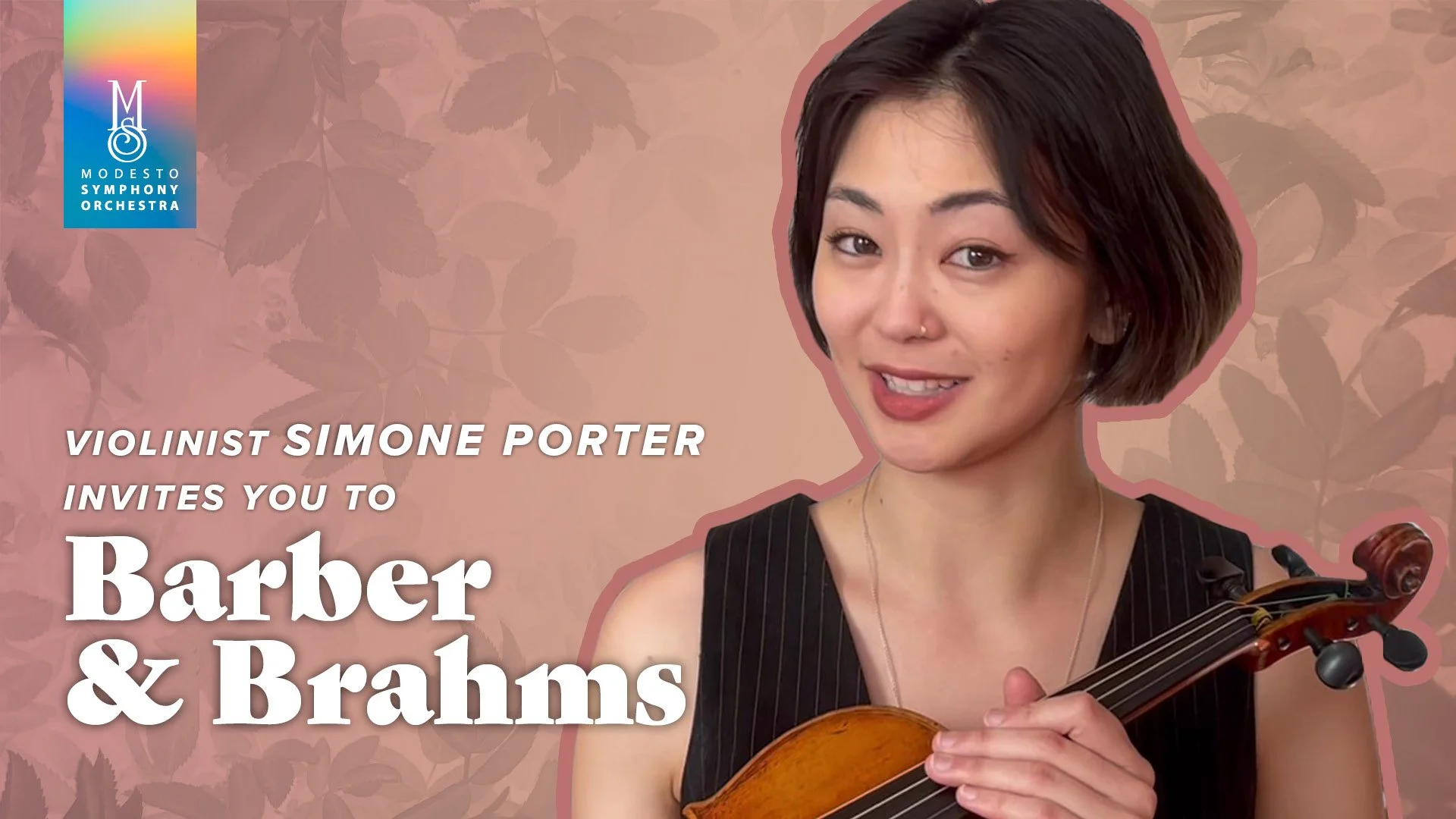

Program Notes: Barber & Brahms

Notes about:

Brouwer’s Remembrances

Barber’s Violin Concerto

Brahms’ Symphony No. 2 in D major

Program Notes for February 10 & 11, 2023

Barber & Brahms

Margaret Brouwer

Remembrances

Composer: born February 8, 1940, in Ann Arbor, Michigan

Composed: 1996

written for the Roanoke Symphony, dedicated to Robert Stewart

Premiere: Roanoke Symphony, Yong-Yan Hu, guest conductor, Roanoke, VA, March 18, 1996

Duration: 14 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 (2nd picc.) 2 EH 2 2(2nd cbsn.); 4331; timp., 2 perc., hp., strings

This tone poem is an elegy and a tribute to Robert Stewart who was a musician, composer, sailor and loved one. Beginning with an expression of grief and sorrow, the music evolves into a musical portrait, full of warm memories, love and admiration, and images of sailing. Typical of elegies and tone poems, such as "Death and Transfiguration" by Strauss, it ends in a spirit of consolation and hope.

REVIEWS

"...Next was RSO Composer- in-Residence Margaret Brouwer's lovely tone poem "Remembrances." This was Brouwer at her best: lyrical, accessible, powerful and deeply moving. I have heard a number of Brouwer's works in several venues, and "Remembrances" made the best impression by a long shot. If more contemporary composers would write like Brouwer in this vein, the uneasy armed truce between audiences and modern music would quickly come to an end....In the long second section there were numerous gorgeous solos for winds, including a ravishing line from solo oboe over timpani roll and pedal tones from the double basses. There was also a lovely soliloquy for clarinet. The mood alternated between gentle sorrow and striving affirmation. "Remembrances" ended on a rising three-note figure and the piece was quickly awarded enthusiastic applause, bravos and a standing ovation." - Seth Williamson, Roanoke Times, March 19, 1996

"The moving "Remembrances" is 'an elegy and a tribute' to a deceased loved one. Its 15-minute span allows it to move with unhurried sincerity from mourning to hard-won reassurance. With its consonant tonality, it is the most stereotypical "American" piece on this disc." - Raymond S Tuttle, International Record Review, June 2006

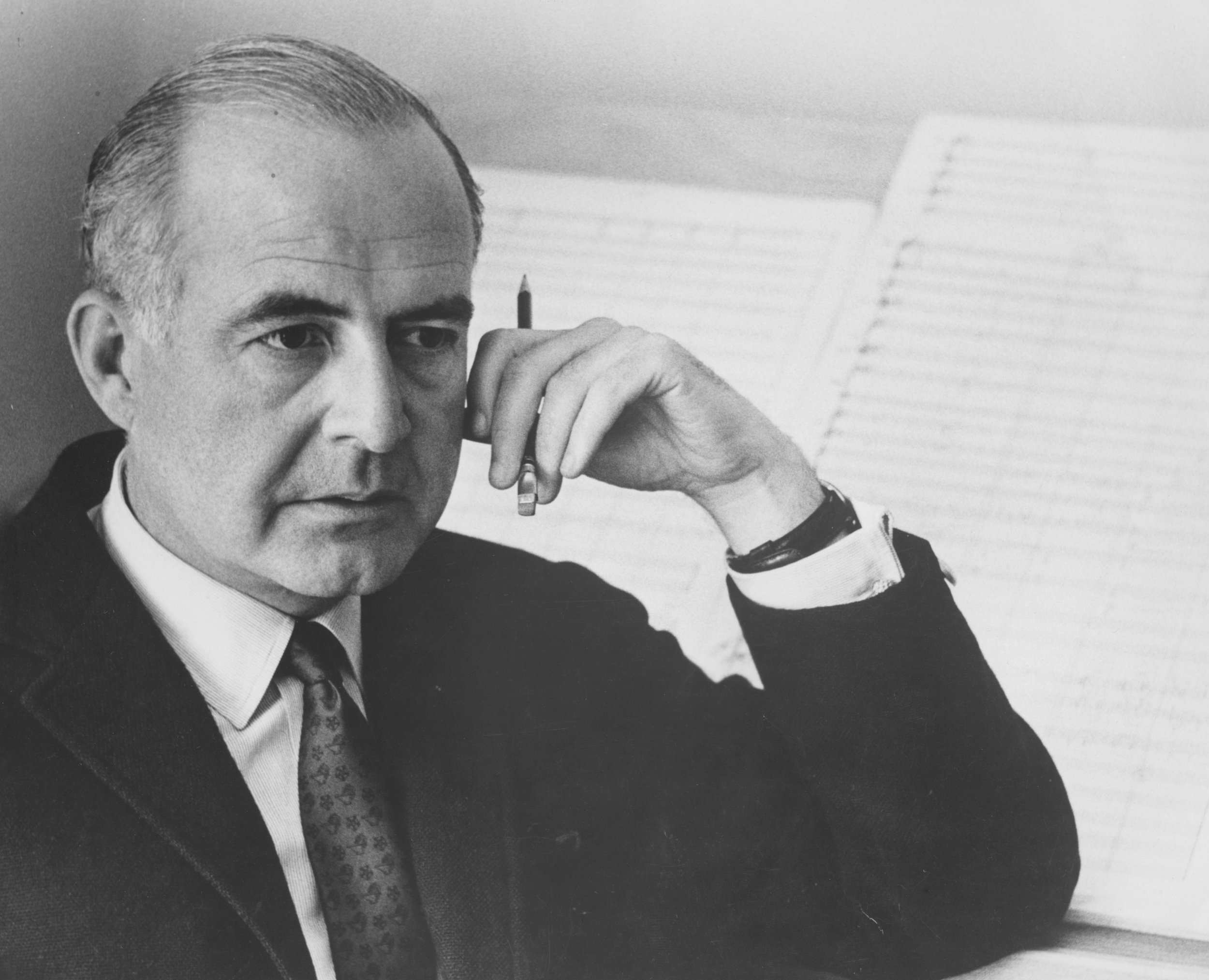

Samuel Barber

Violin Concerto, op. 14

Composer: born March 9, 1910, West Chester, PA; died January 23, 1981, New York City

Work composed: 1939, rev. 1948

World premiere: Eugene Ormandy led the Philadelphia Orchestra, with violinist Albert Spalding, on February 7, 1941. The revised version was first performed by violinist Ruth Posselt, with Serge Koussevitzky leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on January 6, 1949.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, snare drum, piano, and strings

Estimated duration: 25 minutes

Samuel Barber wrote the Violin Concerto, his first major commission, for Samuel Fels, the inventor of Fels Naptha soap, on behalf Fels’ adopted son, violinist Iso Briselli. Barber began work on the concerto in Switzerland in the summer of 1939, but, due to what he described in a letter as “increasing war anxiety,” Barber left Europe in August and returned home with the final movement still unfinished.

At the end of summer 1939, Barber sent the first two movements to Briselli for comment. Briselli was unimpressed, describing them as “too simple and not brilliant enough for a concerto.” Taking these comments to heart, Barber resolved to write a final movement that would afford “ample opportunity to display the artist’s technical powers.” Briselli found fault with this movement as well, calling it “too lightweight” in comparison with the other movements. In a letter to Fels, Barber wrote, “[I am] sorry not to have given Iso what he had hoped for, but I could not destroy a movement in which I have complete confidence, out of artistic sincerity to myself. So we decided to abandon the project, with no hard feelings on either side.” Barber later approached violinist Albert Spalding, who immediately agreed to premiere the work. Because of all the controversy generated by the third movement, Barber gave the concerto a humorous nickname, the “concerto del sapone,” or a “soap concerto,” a reference both to Fels Naptha and the melodrama of soap operas.

Reviews praised the concerto as “an exceptional popular success” and Barber for writing a concerto “refreshingly free from arbitrary tricks and musical mannerisms … straightforwardness and sincerity are among its most engaging qualities.” The late annotator Michael Steinberg called the opening of the first movement “magical,” and goes on to ask, “Does any other violin concerto begin with such immediacy and with so sweet and elegant a melody?” Few works, certainly few concertos, draw the listener in so quickly, and keep our attention focused so completely. The Andante semplice features a heartbreakingly beautiful oboe solo – classic Barber in its yearning – and the violinist answers it with an impassioned yet surprisingly intimate melody that suggests the violin musing aloud to itself.

The finale, a rondo theme and variations, is particularly impressive. In his program notes for the 1941 premiere, Barber wrote, with characteristic understatement, “The last movement, a perpetual motion, exploits the more brilliant and virtuoso characteristics of the violin.” But as biographer Barbara Heyman points out, “This is one of the few virtually nonstop concerto movements in the violin literature (the solo instrument plays for 110 measures without interruption).”

Watch to learn more about Barber’s Violin Concert from violinist Simone Porter!

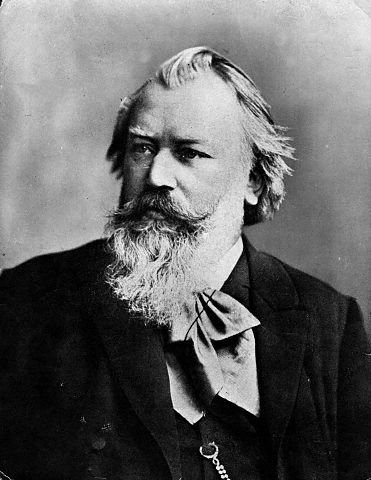

JOhannes Brahms

Symphony No. 2 in D major, op. 73

Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Work composed: During the summer and fall of 1877

World premiere: Hans Richter led the Vienna Philharmonic on December 30, 1877

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration:39 minutes

Less than a year after the successful premiere of Johannes Brahms’ first symphony, on November 4, 1876, the composer left Vienna to spend the summer at the lakeside town of Pörtschach on Lake Wörth, in southern Austria. There, in the beauty and quiet of the countryside, Brahms completed his second symphony. Pörtschach was to be a productive place for Brahms; over the course of three summers there he wrote several important works, including his Violin Concerto. In a letter to critic Eduard Hanslick, a lifelong Brahms supporter, Brahms wrote, “The melodies fly so thick here that you have to be careful not to step on one.”

Unlike Brahms’ first symphony, which took more than 20 years to complete, work on the second went smoothly, and Brahms finished it in just four months. Brahms felt so good about his progress that he joked with his publisher, “The new symphony is so melancholy that you won’t stand it. I have never written anything so sad … the score must appear with a black border.” In a different letter, Brahms self-mockingly observed, “Whether I have a pretty symphony I don’t know; I must ask clever people sometime.”

As Brahms composed, he shared his work-in-progress with lifelong friend Clara Schumann. “Johannes came this evening and played me the first movement of his Second Symphony in D major, which greatly delighted me,” Schumann noted in her diary in October 1877. “I find it in invention more significant than the first movement of the First Symphony … I also heard a part of the last movement and am quite overjoyed with it. With this symphony he will have a more telling success with the public as well than he did with the First, much as musicians are captivated by the latter through its inspiration and wonderful working-out.”

The Symphony No. 2 is often described as the cheerful alter ego to the solemn melancholy of the Symphony No. 1. Brahms uses the lilting notes of the Allegro non troppo as a common link throughout all four movements, where they are repeated, reversed and otherwise, in Schumann’s words, “wonderfully worked-out.” In the extended coda, Brahms introduces the trombones and tuba, casting a tiny shadow over the sunny mood. The Adagio’s lyrical cello melody hints at the wistful melancholy that characterizes so much of Brahms’ music. The Allegretto grazioso is remarkably gentle, and the infectious joy of the closing Allegro con spirito expands on the first movement’s amiable mood, so much so that at the Vienna premiere, the audience demanded an encore.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Notes about:

Golijov’s Sidereus

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Program Notes for April 1 & 2, 2022

Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Osvaldo Golijov

Sidereus

Composer: born December 5, 1960, La Plata, Argentina

Work composed: 2010; co-commissioned by 36 orchestras to honor the career of Henry Fogel, former President and CEO of the League of American Orchestras.

World premiere: Mei-Ann Chen led the Memphis Symphony Orchestra at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts in Memphis, TN, on October 16, 2010.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, piccolo trumpet, trombone, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 9 minutes

Since 2000, when Osvaldo Golijov’s La Pasión según San Marcos (St. Mark Passion) premiered, he and his music have been at the forefront of the contemporary music world; The Boston Globe hailed La Pasión as “the first indisputably great composition of the 21st century.” Golijov has also received acclaim for other groundbreaking works such as his opera Ainadamar; the clarinet quintet The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind; several works for Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble; vocal music for soprano Dawn Upshaw; and scores he has written for the films of Francis Ford Coppola. In the fall of 2021, Golijov’s latest work, Um Dia Bom, for the string quartet Brooklyn Rider, premiered in Boston. Golijov is currently the Loyola Professor of Music at College of the Holy Cross, where he has taught since 1991.

The title Sidereus comes from the 17th-century Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, whose 1610 treatise Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger) described his detailed telescopic observations of the surface of the moon. “With these discoveries, the moon was no longer the province of poets exclusively,” Golijov said in an interview. “It had also become an object of inquiry: Could there be water there? Life? If there was life, then the Vatican was scared, because, as Cardinal Bellarmino wrote to Galileo: How were the people there created? How would their souls be saved? What do we do about Adam? Wasn’t he supposed to be the first man? How do we explain the origin of possible life elsewhere? What about his rib? It’s the duality: the moon is still good for love and lovers and poets, but a scientific observation can lead us to entirely new realizations.”

Two years after its premiere, composer and critic Tom Manoff heard the Eugene Symphony perform Sidereus, and noticed an uncanny resemblance between it and Barbeich, a solo work for accordion by Michael Ward-Bergeman. In his blog, Manoff accused Golijov of plagiarism. A number of other well-known critics latched on to the story, and a major controversy ensued.

As it happens, Golijov and Ward-Bergeman are friends and long-time creative collaborators, and some of the music in both Barbeich and Sidereus comes from deleted sections of a film score the two men had co-written. “Osvaldo and I came to an agreement regarding the use of Barbeich for Sidereus,” Ward-Bergeman explained. “The terms were clearly understood, and we were both happy to agree.”

SErgei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Composer: April 27, 1891, Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine; died March 4, 1953, Moscow

Work composed: 1916-21; dedicated to poet Konstantin Balmont.

World premiere: Frederick Stock led the Chicago Symphony with the composer at the piano on December 16, 1921.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, tambourine, and strings.

Estimated duration: 28 minutes

American journalist: “What is a classical composer?”

Sergei Prokofiev: “He is a mad creature who composes work incomprehensible to people of his own generation. He has discovered a certain logic, as yet unknown to others, so that they cannot follow him. Only later do the roads that he has pointed out, if they are good ones, become understandable to those around him.”

In his memoirs, Sergei Prokofiev said he “wished to poke a little fun at the Americans,” when asked the question quoted above in a 1927 interview he gave in New York. Prokofiev’s tongue-in-cheek response was more accurate than he intended, however, particularly with regard to his own music and how it was received by American audiences.

Prokofiev composed in a patchwork style, jotting down fragments of themes in a notebook as they came to him. Prokofiev kept these musical diaries for years, and often referred to them when he composed. Several of Prokofiev’s musical ideas for the Third Piano Concerto had been gestating since 1913, including the delicate melody that forms the basis for the Andantino theme and variations. Like a quilt design fashioned from many unrelated patches, Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto is an artful arrangement of musical ideas that evolve into a unified sound collage. Prokofiev put the finishing touches on the third concerto during the summer of 1921, while he was living in St. Brevin-les-Pins, on the northwest coast of France.

The Andante-Allegro contrasts the languid opening clarinet melody with the piano’s ebullient energy. The final theme, a rapidly ascending stampede of thirds in the piano, was one of the first fragments Prokofiev wrote almost a decade earlier. The theme of the Tema con variazioni (Theme with variations) is a lilting, rhythmic melody first heard in the winds; the five variations that follow are, by turns, wistfully elegant, agitated, stormy, mysterious, and frenzied. Prokofiev characterized the Allegro ma non troppo as an “argument” between piano and orchestra, full of “caustic humor … with frequent differences of opinion as regards key.” After much musical bickering, the concerto ends with a blazing coda.

The exuberant, brash Piano Concerto No. 3 drew thunderous applause from American audiences but rather tepid reviews. After the premiere, one Chicago paper described it as “a plum pudding without the plums.” Later concerts in New York produced similar reactions; Prokofiev’s observation about the “certain logic” of contemporary composers proved prescient. Three years after the end of WWI, which disrupted all societal and cultural conventions, audiences were receptive to Prokofiev’s post-war explorations of new sonorities, but critics, often more conservative than their readers, were not. Discouraged by the lackluster American reviews of his music, Prokofiev departed for Europe. In 1932, he made his first recording, playing the Third Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra. This recording helped make the Third Piano Concerto one of Prokofiev’s most popular works.

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Work composed: Brahms began working on his first symphony in 1856 and returned to it periodically over the next 19 years. He wrote the bulk of the music between 1874 and 1876.

World premiere: Otto Dessoff led the Badische Staatskapelle in Karlsruhe, on November 4, 1876.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Estimated duration: 42 minutes

““There are fewer things heavier than the burden of a great potential.” ”

In 1853, Robert Schumann wrote a laudatory article about an unknown 20-year-old composer from Hamburg named Johannes Brahms, whom, Schumann declared, was the heir to Beethoven’s musical legacy. Schumann wrote, “If [Brahms] directs his magic wand where the massed power in chorus and orchestra might lend him their strength, we can look forward to even more wondrous glimpses into the secret world of the spirits.” At the time Schumann’s piece was published, Brahms had composed several chamber pieces and works for piano, but nothing for orchestra. The article brought Brahms to the attention of the musical world, but it also dropped a crushing weight of expectation onto his young shoulders. “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it feels to hear behind you the tramp of a giant like Beethoven,” Brahms grumbled.

Because Brahms took almost 20 years to complete what became his Op. 68, one might suppose its long gestation stemmed from Brahms’ possible trepidation about producing a symphony worthy of the Beethovenian ideal. This assumption, on its own, does Brahms a disservice. Daunting though the task might have been, Brahms also wanted to take his time. This measured approach reflects the high regard Brahms had for the symphony as a genre. “Writing a symphony is no laughing matter,” he remarked.

Brahms began sketching the first movement when he was 23, but soon realized he was handicapped by his lack of experience composing for an orchestra. Over the next 19 years, as he continued working on Op. 68, Brahms wrote several other orchestral works, including the 1868 German Requiem and the popular 1873 Variations on a Theme by Haydn (aka the St. Anthony Variations). The enthusiastic response that greeted both works bolstered Brahms’ confidence in his ability to handle orchestral writing. In 1872, Brahms was offered the conductor’s post at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music). This opportunity to work directly with an orchestra gave Brahms the invaluable first-hand experience he needed. 23 years after Schumann’s article first appeared, Brahms premiered his Symphony No. 1 in C minor. It was worth the wait.

Brahms’ friend, the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick, summed up the feelings of many: “Seldom, if ever, has the entire musical world awaited a composer’s first symphony with such tense anticipation … The new symphony is so earnest and complex, so utterly unconcerned with common effects, that it hardly lends itself to quick understanding … [but] even the layman will immediately recognize it as one of the most distinctive and magnificent works of the symphonic literature.”

Hanslick’s reference to the symphony’s complexity was a polite way of saying the music was too serious to appeal to the average listener, but Brahms was unconcerned; he was not trying to woo the public with pretty sounds. “My symphony is long and not exactly lovable,” he acknowledged. The symphony is carefully crafted; one can hear Brahms’ compositional thought processes throughout, especially his decision to incorporate several overt references to Beethoven. The moody, portentous atmosphere of the first movement, and the short thematic fragments from which Brahms spins out seemingly endless developments, are all hallmarks of Beethoven’s style. Brahms also references Beethoven by choosing the key of C minor, which is closely associated with several of Beethoven’s major works, including the Fifth Symphony, Egmont Overture, and Piano Concerto No. 3. And yet, despite all these deliberate nods to Beethoven, this symphony is not, as conductor Hans von Bülow dubbed it, “Beethoven’s Tenth.” The voice is distinctly Brahms’, especially in the inner movements.

The tender, wistful Andante sostenuto contrasts the brooding power of the first movement. Brahms weaves a series of dialogues among different sections of the orchestra, and concludes with a duet for solo violin and horn. In the Allegretto, Brahms slows down Beethoven’s frantic scherzo tempos. The pace is relaxed, easy, featuring lilting themes for strings and woodwinds. The finale’s strong, confident horn solo proclaims Brahms’ victory over the doubts that beset him during Op. 68’s long incubation. Here Brahms also pays his most direct homage to Beethoven, with a majestic theme, first heard in the strings, that closely resembles the “Ode to Joy” melody from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When a listener remarked on this similarity, Brahms snapped irritably, “Any jackass could see that!”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com