Program Notes: Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Program Notes for April 1 & 2, 2022

Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Osvaldo Golijov

Sidereus

Composer: born December 5, 1960, La Plata, Argentina

Work composed: 2010; co-commissioned by 36 orchestras to honor the career of Henry Fogel, former President and CEO of the League of American Orchestras.

World premiere: Mei-Ann Chen led the Memphis Symphony Orchestra at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts in Memphis, TN, on October 16, 2010.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, piccolo trumpet, trombone, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 9 minutes

Since 2000, when Osvaldo Golijov’s La Pasión según San Marcos (St. Mark Passion) premiered, he and his music have been at the forefront of the contemporary music world; The Boston Globe hailed La Pasión as “the first indisputably great composition of the 21st century.” Golijov has also received acclaim for other groundbreaking works such as his opera Ainadamar; the clarinet quintet The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind; several works for Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble; vocal music for soprano Dawn Upshaw; and scores he has written for the films of Francis Ford Coppola. In the fall of 2021, Golijov’s latest work, Um Dia Bom, for the string quartet Brooklyn Rider, premiered in Boston. Golijov is currently the Loyola Professor of Music at College of the Holy Cross, where he has taught since 1991.

The title Sidereus comes from the 17th-century Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, whose 1610 treatise Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger) described his detailed telescopic observations of the surface of the moon. “With these discoveries, the moon was no longer the province of poets exclusively,” Golijov said in an interview. “It had also become an object of inquiry: Could there be water there? Life? If there was life, then the Vatican was scared, because, as Cardinal Bellarmino wrote to Galileo: How were the people there created? How would their souls be saved? What do we do about Adam? Wasn’t he supposed to be the first man? How do we explain the origin of possible life elsewhere? What about his rib? It’s the duality: the moon is still good for love and lovers and poets, but a scientific observation can lead us to entirely new realizations.”

Two years after its premiere, composer and critic Tom Manoff heard the Eugene Symphony perform Sidereus, and noticed an uncanny resemblance between it and Barbeich, a solo work for accordion by Michael Ward-Bergeman. In his blog, Manoff accused Golijov of plagiarism. A number of other well-known critics latched on to the story, and a major controversy ensued.

As it happens, Golijov and Ward-Bergeman are friends and long-time creative collaborators, and some of the music in both Barbeich and Sidereus comes from deleted sections of a film score the two men had co-written. “Osvaldo and I came to an agreement regarding the use of Barbeich for Sidereus,” Ward-Bergeman explained. “The terms were clearly understood, and we were both happy to agree.”

SErgei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Composer: April 27, 1891, Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine; died March 4, 1953, Moscow

Work composed: 1916-21; dedicated to poet Konstantin Balmont.

World premiere: Frederick Stock led the Chicago Symphony with the composer at the piano on December 16, 1921.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, tambourine, and strings.

Estimated duration: 28 minutes

American journalist: “What is a classical composer?”

Sergei Prokofiev: “He is a mad creature who composes work incomprehensible to people of his own generation. He has discovered a certain logic, as yet unknown to others, so that they cannot follow him. Only later do the roads that he has pointed out, if they are good ones, become understandable to those around him.”

In his memoirs, Sergei Prokofiev said he “wished to poke a little fun at the Americans,” when asked the question quoted above in a 1927 interview he gave in New York. Prokofiev’s tongue-in-cheek response was more accurate than he intended, however, particularly with regard to his own music and how it was received by American audiences.

Prokofiev composed in a patchwork style, jotting down fragments of themes in a notebook as they came to him. Prokofiev kept these musical diaries for years, and often referred to them when he composed. Several of Prokofiev’s musical ideas for the Third Piano Concerto had been gestating since 1913, including the delicate melody that forms the basis for the Andantino theme and variations. Like a quilt design fashioned from many unrelated patches, Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto is an artful arrangement of musical ideas that evolve into a unified sound collage. Prokofiev put the finishing touches on the third concerto during the summer of 1921, while he was living in St. Brevin-les-Pins, on the northwest coast of France.

The Andante-Allegro contrasts the languid opening clarinet melody with the piano’s ebullient energy. The final theme, a rapidly ascending stampede of thirds in the piano, was one of the first fragments Prokofiev wrote almost a decade earlier. The theme of the Tema con variazioni (Theme with variations) is a lilting, rhythmic melody first heard in the winds; the five variations that follow are, by turns, wistfully elegant, agitated, stormy, mysterious, and frenzied. Prokofiev characterized the Allegro ma non troppo as an “argument” between piano and orchestra, full of “caustic humor … with frequent differences of opinion as regards key.” After much musical bickering, the concerto ends with a blazing coda.

The exuberant, brash Piano Concerto No. 3 drew thunderous applause from American audiences but rather tepid reviews. After the premiere, one Chicago paper described it as “a plum pudding without the plums.” Later concerts in New York produced similar reactions; Prokofiev’s observation about the “certain logic” of contemporary composers proved prescient. Three years after the end of WWI, which disrupted all societal and cultural conventions, audiences were receptive to Prokofiev’s post-war explorations of new sonorities, but critics, often more conservative than their readers, were not. Discouraged by the lackluster American reviews of his music, Prokofiev departed for Europe. In 1932, he made his first recording, playing the Third Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra. This recording helped make the Third Piano Concerto one of Prokofiev’s most popular works.

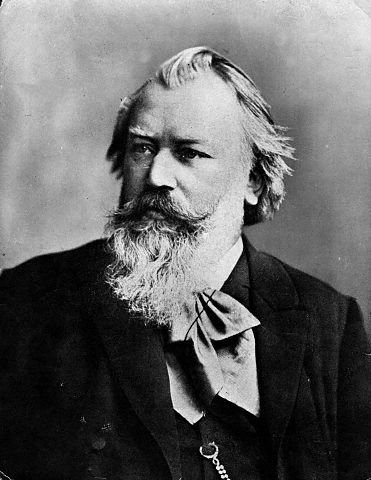

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Work composed: Brahms began working on his first symphony in 1856 and returned to it periodically over the next 19 years. He wrote the bulk of the music between 1874 and 1876.

World premiere: Otto Dessoff led the Badische Staatskapelle in Karlsruhe, on November 4, 1876.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Estimated duration: 42 minutes

““There are fewer things heavier than the burden of a great potential.” ”

In 1853, Robert Schumann wrote a laudatory article about an unknown 20-year-old composer from Hamburg named Johannes Brahms, whom, Schumann declared, was the heir to Beethoven’s musical legacy. Schumann wrote, “If [Brahms] directs his magic wand where the massed power in chorus and orchestra might lend him their strength, we can look forward to even more wondrous glimpses into the secret world of the spirits.” At the time Schumann’s piece was published, Brahms had composed several chamber pieces and works for piano, but nothing for orchestra. The article brought Brahms to the attention of the musical world, but it also dropped a crushing weight of expectation onto his young shoulders. “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it feels to hear behind you the tramp of a giant like Beethoven,” Brahms grumbled.

Because Brahms took almost 20 years to complete what became his Op. 68, one might suppose its long gestation stemmed from Brahms’ possible trepidation about producing a symphony worthy of the Beethovenian ideal. This assumption, on its own, does Brahms a disservice. Daunting though the task might have been, Brahms also wanted to take his time. This measured approach reflects the high regard Brahms had for the symphony as a genre. “Writing a symphony is no laughing matter,” he remarked.

Brahms began sketching the first movement when he was 23, but soon realized he was handicapped by his lack of experience composing for an orchestra. Over the next 19 years, as he continued working on Op. 68, Brahms wrote several other orchestral works, including the 1868 German Requiem and the popular 1873 Variations on a Theme by Haydn (aka the St. Anthony Variations). The enthusiastic response that greeted both works bolstered Brahms’ confidence in his ability to handle orchestral writing. In 1872, Brahms was offered the conductor’s post at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music). This opportunity to work directly with an orchestra gave Brahms the invaluable first-hand experience he needed. 23 years after Schumann’s article first appeared, Brahms premiered his Symphony No. 1 in C minor. It was worth the wait.

Brahms’ friend, the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick, summed up the feelings of many: “Seldom, if ever, has the entire musical world awaited a composer’s first symphony with such tense anticipation … The new symphony is so earnest and complex, so utterly unconcerned with common effects, that it hardly lends itself to quick understanding … [but] even the layman will immediately recognize it as one of the most distinctive and magnificent works of the symphonic literature.”

Hanslick’s reference to the symphony’s complexity was a polite way of saying the music was too serious to appeal to the average listener, but Brahms was unconcerned; he was not trying to woo the public with pretty sounds. “My symphony is long and not exactly lovable,” he acknowledged. The symphony is carefully crafted; one can hear Brahms’ compositional thought processes throughout, especially his decision to incorporate several overt references to Beethoven. The moody, portentous atmosphere of the first movement, and the short thematic fragments from which Brahms spins out seemingly endless developments, are all hallmarks of Beethoven’s style. Brahms also references Beethoven by choosing the key of C minor, which is closely associated with several of Beethoven’s major works, including the Fifth Symphony, Egmont Overture, and Piano Concerto No. 3. And yet, despite all these deliberate nods to Beethoven, this symphony is not, as conductor Hans von Bülow dubbed it, “Beethoven’s Tenth.” The voice is distinctly Brahms’, especially in the inner movements.

The tender, wistful Andante sostenuto contrasts the brooding power of the first movement. Brahms weaves a series of dialogues among different sections of the orchestra, and concludes with a duet for solo violin and horn. In the Allegretto, Brahms slows down Beethoven’s frantic scherzo tempos. The pace is relaxed, easy, featuring lilting themes for strings and woodwinds. The finale’s strong, confident horn solo proclaims Brahms’ victory over the doubts that beset him during Op. 68’s long incubation. Here Brahms also pays his most direct homage to Beethoven, with a majestic theme, first heard in the strings, that closely resembles the “Ode to Joy” melody from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When a listener remarked on this similarity, Brahms snapped irritably, “Any jackass could see that!”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com