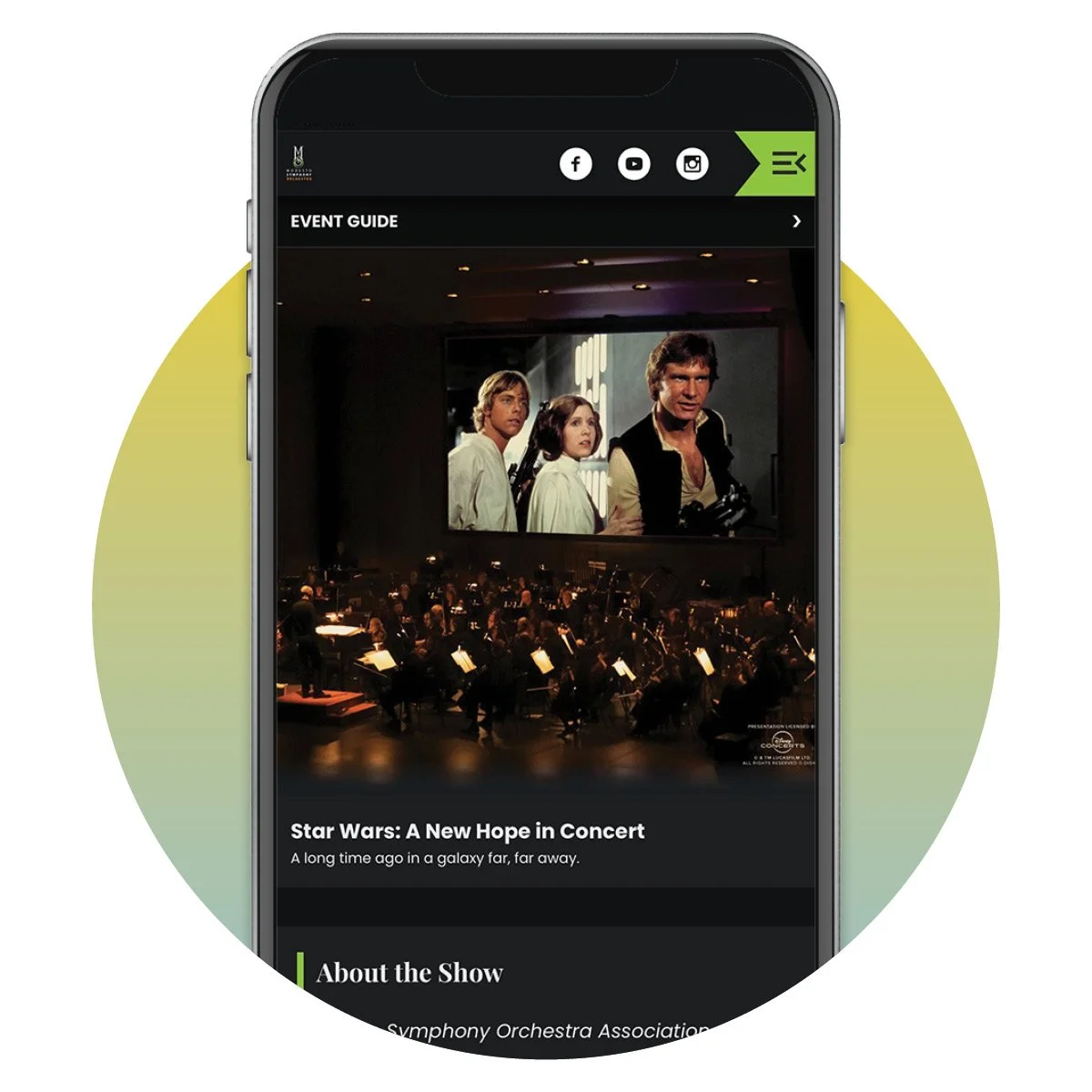

Star Wars: A New Hope in Concert

June 3, 2022 at 7:30 pm

June 4, 2022 at 2:00 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Star Wars: A New Hope in Concert

Friday, June 3, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, June 4, 2022 at 2:00 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

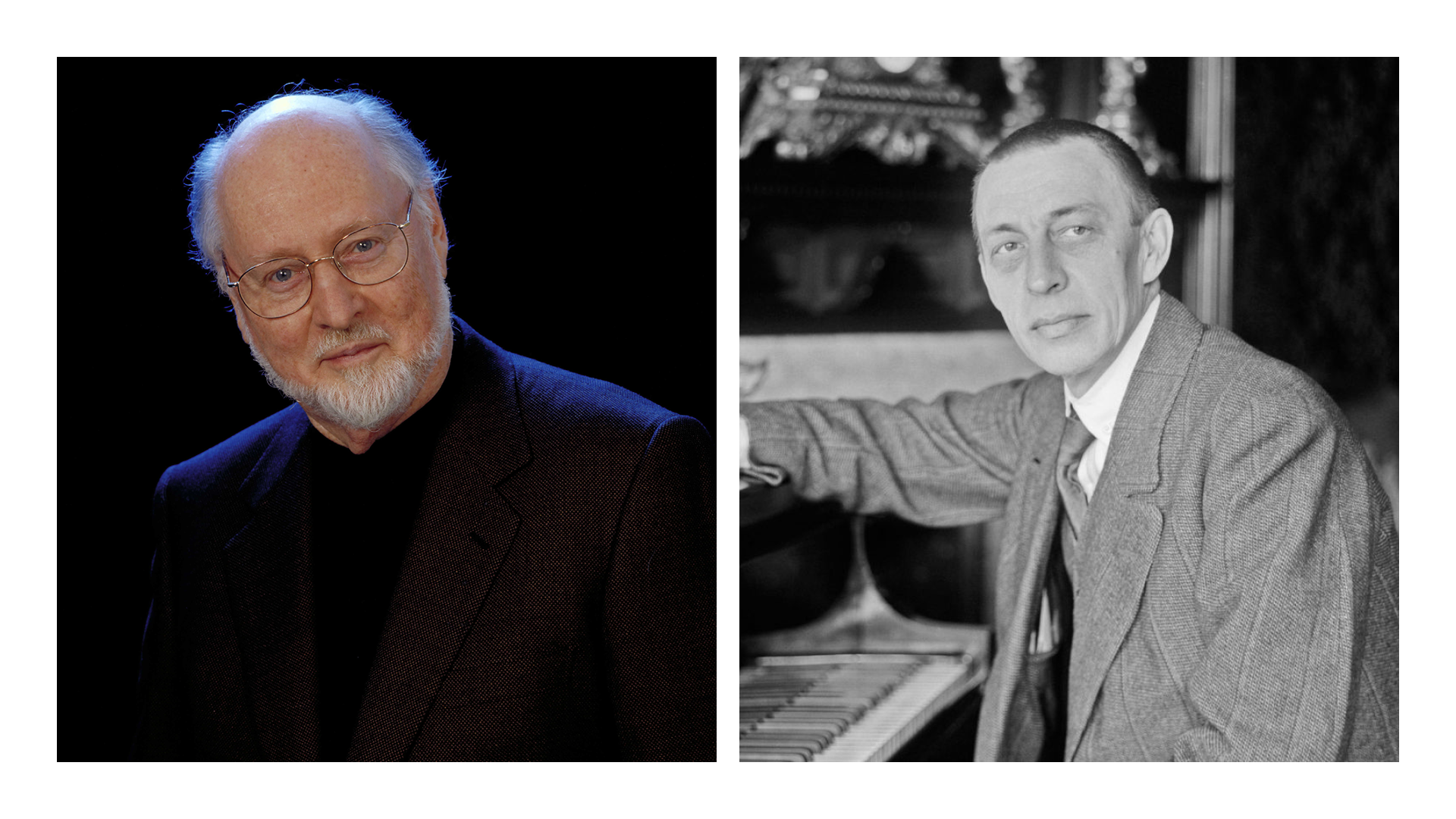

John Williams (b. 1932)

Star Wars: A New Hope

Feature Film with Orchestra

There will be one intermission.

Presentation licensed by Disney Concerts in association with 20th Century Fox, Lucasfilm Ltd., and Warner/Chappell Music. All rights reserved.

Star Wars Film Concert Series

Star Wars: A New Hope

Twentieth Century Fox Presents

A Lucasfilm Ltd. production

Starring

Mark Hamill

Harrison Ford

Carrie Fisher

Peter Cushing

and Alec Guinness

Written and Directed by

George Lucas

Produced by

Gary Kurtz

Music by

John Williams

Panavision

Prints by Deluxe

Technicolor

MPAA PG Rating

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack available at Disneymusicemporium.com

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “JEDI” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

MSYO Season Finale Concert

May 7, 2022 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Season Finale Concert

Concert Orchestra

Donald C. Grishaw, conductor

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to Barber of Seville (1810)

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Concerto for Two Cellos (1720)

Soon Hee Newbold (b.1974)

A Pirate’s Legend (2014)

Morton Stevens (1929-1991)

Hawaii 5-0 (1970)

Intermission

Symphony Orchestra

Wayland Whitney, conductor

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 20 (1772)

Allegro

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Cortege from Mlada (1889-1890)

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to William Tell (1829)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Selections from Swan Lake (1875-1876)

10. Scene

2. Valse

20. Czardas

23. Mazurka

28. Scene

29. Finale

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “MSYO” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

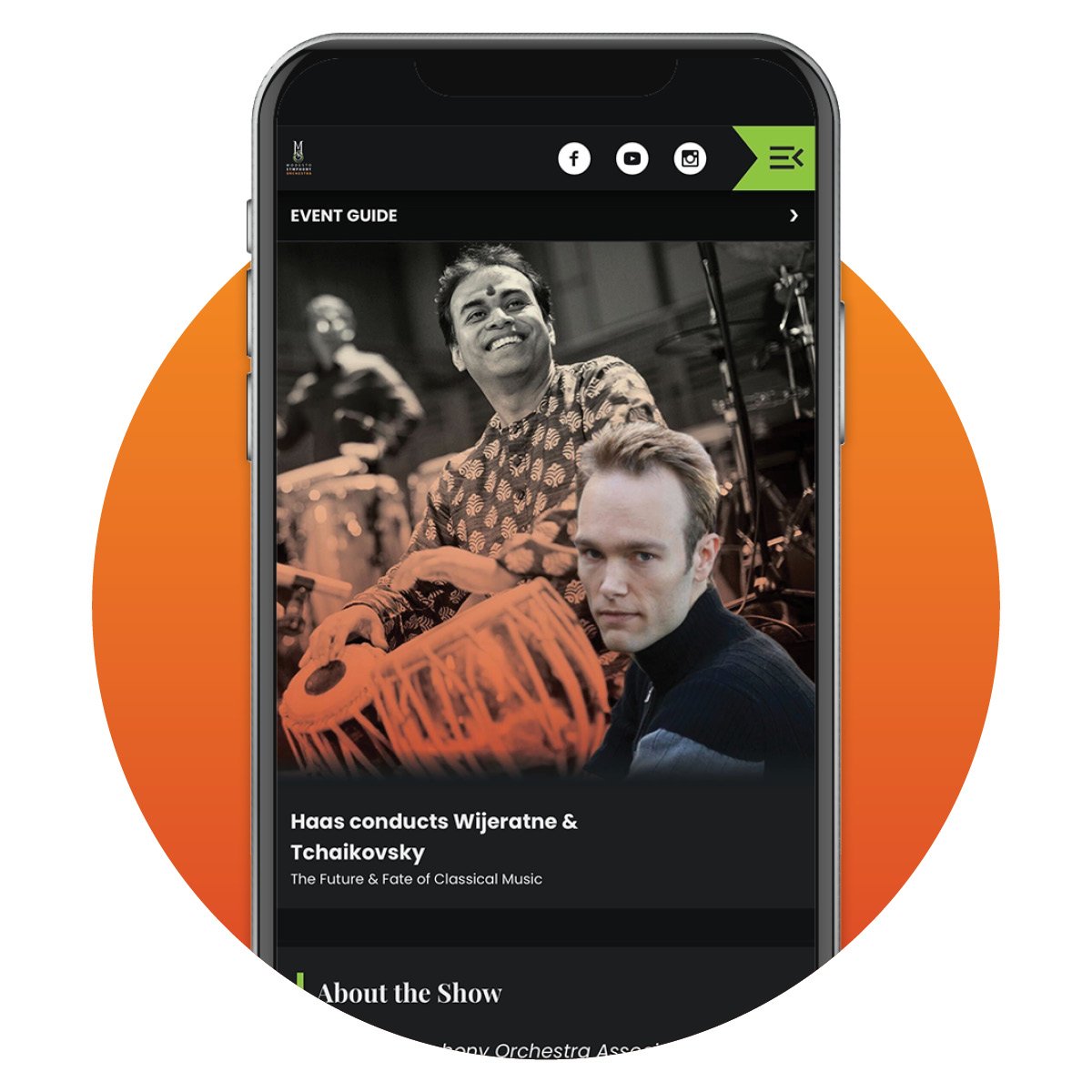

Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

May 6 & 7, 2022 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

Friday, May 6, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, May 7, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Program

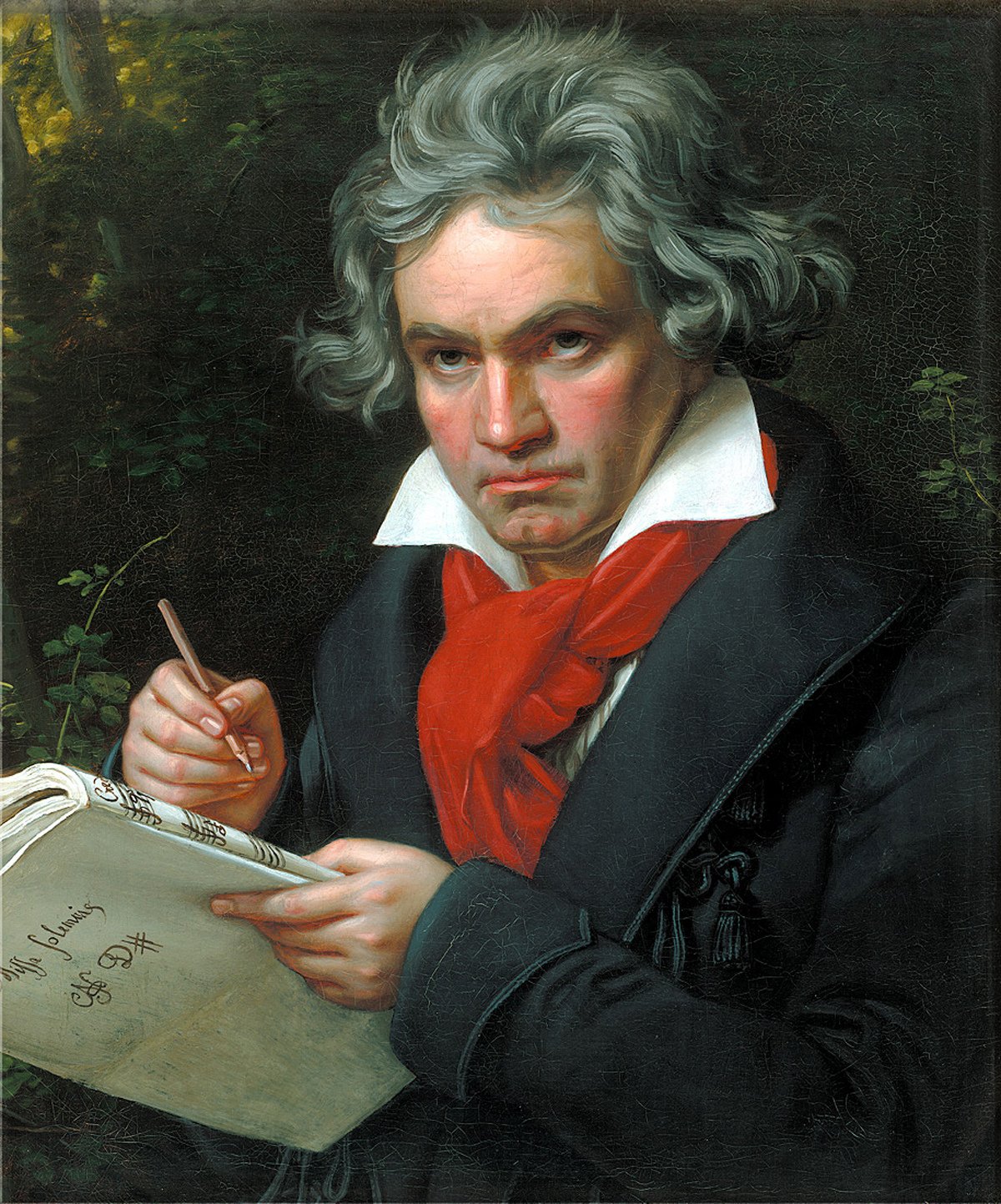

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Coriolan Overture, op. 62 (1807)

Dinuk Wijeratne (b. 1978)

Tabla Concerto (2011)

Sandeep Das, tabla

II. Folk Song : ‘White in the moon the long road lies (that leads me from my love)

I. Canons, Circles

INTERMISSION

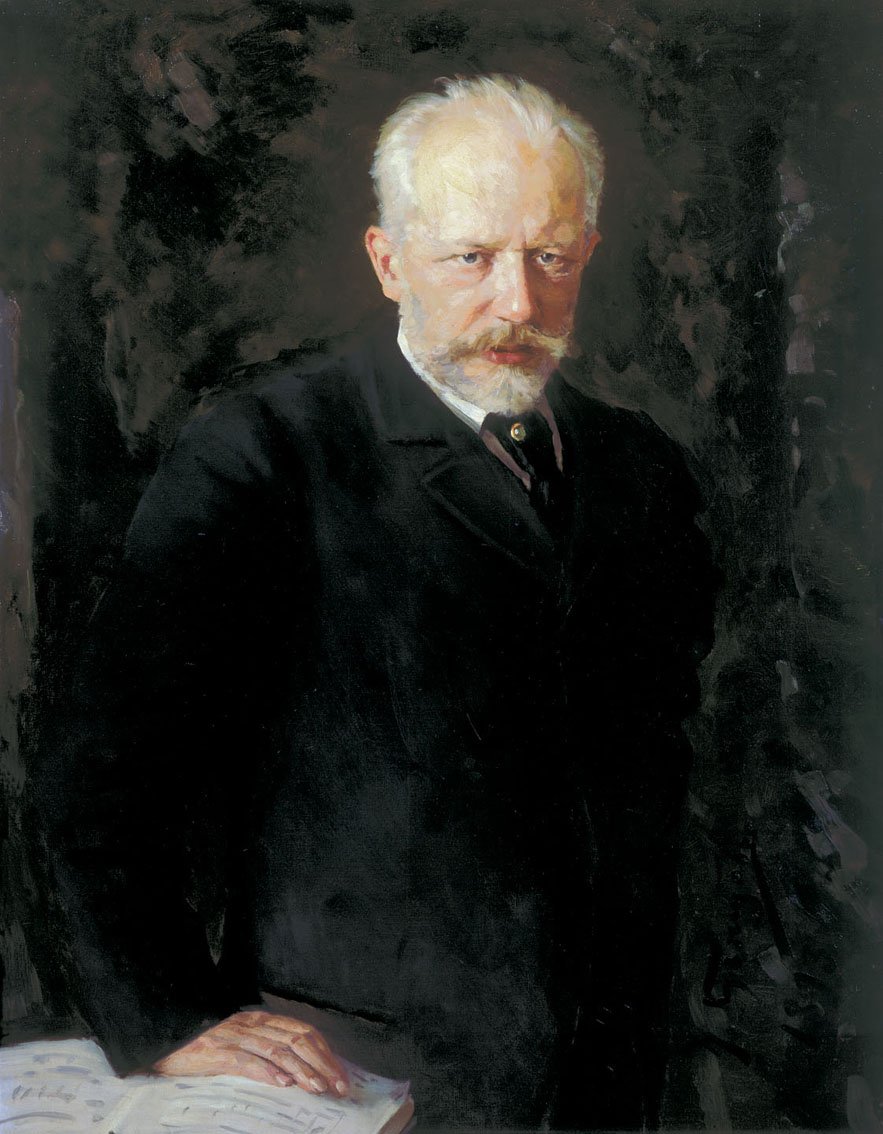

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, op. 36 (1877-1878)

I.Andante Sostenuto- Moderato Con Anima

II. Andantino in modo di canzona

III. Scherzo. Pizzicato ostinato. Allegro

IV. Finale. Allegro con Fuoco

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “TABLA” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

Notes about:

Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, op. 62

Wijeratne’s Tabla Concerto

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 in F minor, op. 36

Program Notes for May 6 & 7, 2022

Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Coriolan Overture, op. 26

Composer: born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

Work composed: 1807

World premiere: Beethoven conducted a private concert in the Vienna palace of his patron, Prince Lobkowitz, in March 1807, in a performance that also included premieres of his Symphony No. 4 and Piano Concerto No. 4.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Most overtures serve as instrumental introductions to operas or plays. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, although inspired by his countryman Heinrich Joseph Collin’s play about the Roman general Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, was a purely orchestral work from its inception. Unfortunately for Collin, his play, unlike Shakespeare’s on the same subject, was not well received in its initial run in 1804, nor its revival three years later.

In Collin’s play, a hubristic Coriolanus declares war on his hometown of Rome, which had exiled him for his inattention to its plebeian citizens. Enraged, Coriolanus enlists the help of Rome’s most fearsome enemies, the Volsci, to storm the city. As Coriolanus approaches at the head of the Volscian armies, Roman officials sue for peace, to no avail. Coriolanus’ wife, Volumnia, along with his mother and his two sons, also beg him to cease fighting. Coriolanus is moved by his family’s entreaties and, overcome with shame at his dishonorable behavior, literally falls on his sword (this differs from Shakespeare’s ending, in which Coriolanus is murdered).

The dramatic elements of Coriolanus’ story inspired Beethoven’s musical imagination. The music traces an emotional arc, contrasting Coriolanus’ fury and bellicosity with Volumnia’s quiet, forceful pleas for peace.

Dinuk Wijeratne

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born 1978, Sri Lanka

Work composed: 2011, commissioned by Symphony Nova Scotia

World premiere: Recorded live by the CBC, February 9th, 2012 at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium, Halifax, Nova Scotia, featuring Ed Hanley (Tabla) & Symphony Nova Scotia conducted by Bernhard Gueller.

*The Tabla Concerto was twice a finalist for the Masterworks Arts Award (2012, 2016).

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling cor anglais), 2 clarinets in B♭ (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 2 horns in F, 2 trumpets in B, 1 trombone, timpani, 2 percussion, harp, strings

Duration: 27 minutes

Composer’s original program notes:

Canons, Circles

Folk song: ‘White in the moon the long road lies (that leads me from my love)’

Garland of Gems

While the origins of the Tabla are somewhat obscure, it is evident that this ‘king’ of Indian percussion instruments has achieved global popularity for the richness of its timbre, and for the virtuosity of a rhythmically complex repertoire that cannot be separated from the instrument itself. In writing a large-scale work for Tabla and Symphony Orchestra, it is my hope to allow each entity to preserve its own aesthetic. Perhaps, at the same time, the stage will be set for some new discoveries.

While steeped in tradition, the Tabla lends itself heartily to innovation, and has shown its cultural versatility as an increasingly sought-after instrument in contemporary Western contexts such as Pop, Film Music, and World Music Fusion. This notion led me to conceive of an opening movement that would do the not-so-obvious by placing the Tabla first in a decidedly non-Indian context. Here, initiated by a quasi-Baroque canon in four parts, the music quickly turns into an evocation of one my favourite genres of electronic music: ‘Drum-&-Bass’, characterised by rapid ‘breakbeat’ rhythms in the percussion. Of course, there are some North-Indian Classical musical elements present. The whole makes for a rather bizarre stew that reflects globalisation, for better or worse!

A brief second movement becomes a short respite from the energy of the outer movements, and offers a perspective of the Tabla as accompanist in the lyrical world of Indian folk-song. Set in ‘dheepchandhi’, a rhythmic cycle of 14 beats, the gently lilting gait of theTabla rhythm supports various melodic fragments that come together to form an ephemeral love-song.

Typically, a Tabla player concluding a solo recital would do so by presenting a sequence of short, fixed (non-improvised) compositions from his/her repertoire. Each mini-composition, multi-faceted as a little gem, would often be presented first in the form of a vocal recitation. The traditional accompaniment would consist of a drone as well as a looping melody outlining the time cycle – a ‘nagma’ – against which the soloist would weave rhythmically intricate patterns of tension and release. I wanted to offer my own take on a such a recital finale, with the caveat that the orchestra is no bystander. In this movement, it is spurred on by the soloist to share in some of the rhythmic complexity. The whole movement is set in ‘teentaal’, or 16-beat cycle, and in another departure from the traditional norm, my nagma kaleidoscopically changes colour from start to finish. I am indebted to Ed Hanley for helping me choose several ‘gems’ from the Tabla repertoire, although we have certainly had our own fun in tweaking a few, not to mention composing a couple from scratch.

© Dinuk Wijeratne 2011

Notes from the Conductor, Paul Haas:

As a conductor, I’m always on the lookout for great new music. I love that feeling of discovery, especially when I can share it with orchestra musicians and a whole auditorium full of audience members. And Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto is one of the best pieces I’ve ever come across: full of life, emotion, and color.

The first time I ever programmed it (4 years ago in Thunder Bay, Canada) I wanted the Tabla Concerto to end the entire concert, and I needed it to leave the audience ecstatic. There was a stumbling block, though: the third movement (the written ending) of the Tabla Concerto is admittedly wonderful and down-to-earth, and the soloist sings in addition to playing the tablas. But it doesn’t end with that true excitement and momentum I was looking for. From my perspective, it’s almost impossible to end a concert with it, especially if you want the audience so excited they jump out of their seats.

But somehow I knew this was the right piece to close with. So I thought and thought, and eventually it hit me. Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto actually IS the perfect closer, but only if you do the first two movements, and in reverse order. So we started with the second movement, and then we ended with the first movement. And it was sensational. So sensational, in fact, that I begged Dinuk to let me conduct it this way for you, tonight. So that we can end the first half of our evening together with that same feeling of excitement we achieved in Thunder Bay.

Dinuk agreed, and the rest is history. I can’t wait to share his incredible music with you.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No.4 in F minor, Op. 36

Composer: born May 7, 1840, Kamsko-Votinsk, Viatka province, Russia; died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg

Work composed: 1877-78. Dedicated to Nadezhda von Meck

World premiere: Nikolai Rubinstein led the Russian Musical Society orchestra on February 22, 1878, in Moscow

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 44 minutes

When a former student from the Moscow Conservatory challenged Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky about the “program” for his fourth symphony, the composer responded, “Of course my symphony is programmatic, but this program is such that it cannot be formulated in words. That would excite ridicule and appear comic … In essence, my symphony is an imitation of Beethoven’s Fifth; i.e., I imitated not the musical ideas, but the fundamental concept.”

In December 1876, Tchaikovsky began an epistolary relationship with Mrs. Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and ardent fan of Tchaikovsky’s music. Mme. von Meck offered to become Tchaikovsky’s patron on the condition that they never meet in person; the introverted Tchaikovsky agreed. Soon after von Meck first wrote to Tchaikovsky, he began the Fourth Symphony. As he worked, Tchaikovsky kept von Meck informed of his progress. He dedicated the Fourth Symphony “to my best friend,” which simultaneously paid tribute to von Meck and insured her privacy.

Six months later, Tchaikovsky encountered Antonina Ivanova Milyukova, a former Conservatory student obsessed with her one-time professor. She sent Tchaikovsky several impassioned letters, which alarmed him; eventually Milyukova threatened to kill herself if Tchaikovsky did not return her affection. This untenable situation, combined with Tchaikovsky’s tortured feelings about his sexual orientation and his desire to silence gossip about it, led to a hasty, ill-advised union. Tchaikovsky fled from Milyukova a month after the wedding (their marriage officially ended after three months, although they were never divorced) and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. He was unable to compose any music for the next three years.

Beginning with the Fourth Symphony, Tchaikovsky launched a musical exploration of the concept of Fate as an inescapable force. In a letter to Mme. von Meck, Tchaikovsky explained, “The introduction is the seed of the whole symphony, undoubtedly the central theme. This is Fate, i.e., that fateful force which prevents the impulse to happiness from entirely achieving its goal, forever on jealous guard lest peace and well-being should ever be attained in complete and unclouded form, hanging above us like the Sword of Damocles, constantly and unremittingly poisoning the soul. Its force is invisible and can never be overcome. Our only choice is to surrender to it, and to languish fruitlessly.”

The Fate motive blasts open the symphony with a mighty proclamation from the brasses and bassoons. “One’s whole life is just a perpetual traffic between the grimness of reality and one’s fleeting dreams of happiness,” Tchaikovsky wrote of this movement. This theme returns later in the movement and at the end of the fourth, a reminder of destiny’s inescapability.

The beauty of the solo oboe that begins the Andantino beckons, and the yearning countermelody of the strings surges with surprising energy before it subsides. In the Scherzo, Tchaikovsky departs from the heaviness of the previous movements with pizzicato strings. Tchaikovsky described this playful movement as a series of “capricious arabesques.”

As in the first movement, the Finale bursts forth with a blaze of sound. Marked Allegro con fuoco (with fire), the music builds to a raging inferno. Abruptly, Fate returns and the symphony concludes with barely controlled frenzy, accented by cymbal crashes.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

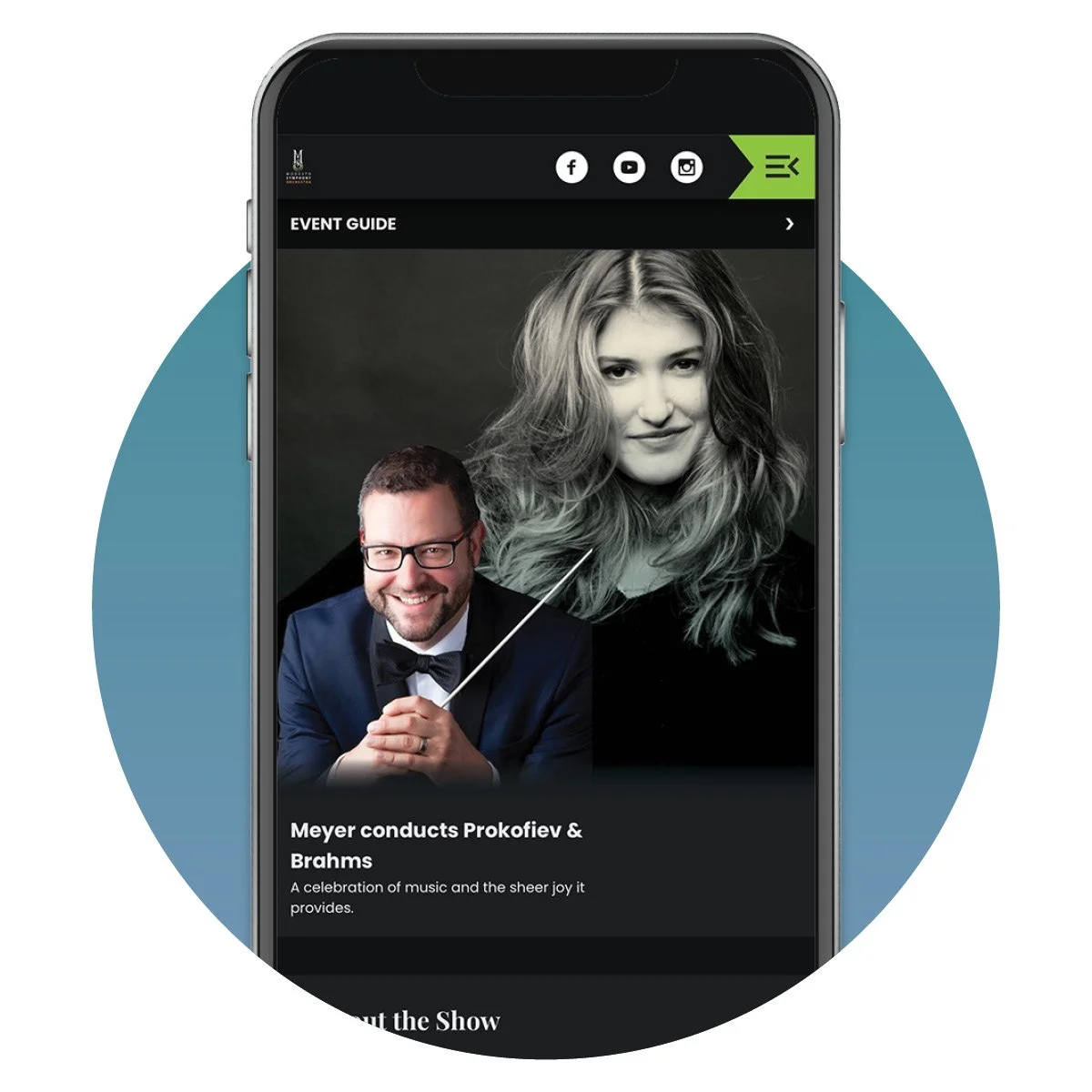

Program Notes: Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Notes about:

Golijov’s Sidereus

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Program Notes for April 1 & 2, 2022

Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Osvaldo Golijov

Sidereus

Composer: born December 5, 1960, La Plata, Argentina

Work composed: 2010; co-commissioned by 36 orchestras to honor the career of Henry Fogel, former President and CEO of the League of American Orchestras.

World premiere: Mei-Ann Chen led the Memphis Symphony Orchestra at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts in Memphis, TN, on October 16, 2010.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, piccolo trumpet, trombone, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 9 minutes

Since 2000, when Osvaldo Golijov’s La Pasión según San Marcos (St. Mark Passion) premiered, he and his music have been at the forefront of the contemporary music world; The Boston Globe hailed La Pasión as “the first indisputably great composition of the 21st century.” Golijov has also received acclaim for other groundbreaking works such as his opera Ainadamar; the clarinet quintet The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind; several works for Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble; vocal music for soprano Dawn Upshaw; and scores he has written for the films of Francis Ford Coppola. In the fall of 2021, Golijov’s latest work, Um Dia Bom, for the string quartet Brooklyn Rider, premiered in Boston. Golijov is currently the Loyola Professor of Music at College of the Holy Cross, where he has taught since 1991.

The title Sidereus comes from the 17th-century Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, whose 1610 treatise Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger) described his detailed telescopic observations of the surface of the moon. “With these discoveries, the moon was no longer the province of poets exclusively,” Golijov said in an interview. “It had also become an object of inquiry: Could there be water there? Life? If there was life, then the Vatican was scared, because, as Cardinal Bellarmino wrote to Galileo: How were the people there created? How would their souls be saved? What do we do about Adam? Wasn’t he supposed to be the first man? How do we explain the origin of possible life elsewhere? What about his rib? It’s the duality: the moon is still good for love and lovers and poets, but a scientific observation can lead us to entirely new realizations.”

Two years after its premiere, composer and critic Tom Manoff heard the Eugene Symphony perform Sidereus, and noticed an uncanny resemblance between it and Barbeich, a solo work for accordion by Michael Ward-Bergeman. In his blog, Manoff accused Golijov of plagiarism. A number of other well-known critics latched on to the story, and a major controversy ensued.

As it happens, Golijov and Ward-Bergeman are friends and long-time creative collaborators, and some of the music in both Barbeich and Sidereus comes from deleted sections of a film score the two men had co-written. “Osvaldo and I came to an agreement regarding the use of Barbeich for Sidereus,” Ward-Bergeman explained. “The terms were clearly understood, and we were both happy to agree.”

SErgei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Composer: April 27, 1891, Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine; died March 4, 1953, Moscow

Work composed: 1916-21; dedicated to poet Konstantin Balmont.

World premiere: Frederick Stock led the Chicago Symphony with the composer at the piano on December 16, 1921.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, castanets, cymbals, tambourine, and strings.

Estimated duration: 28 minutes

American journalist: “What is a classical composer?”

Sergei Prokofiev: “He is a mad creature who composes work incomprehensible to people of his own generation. He has discovered a certain logic, as yet unknown to others, so that they cannot follow him. Only later do the roads that he has pointed out, if they are good ones, become understandable to those around him.”

In his memoirs, Sergei Prokofiev said he “wished to poke a little fun at the Americans,” when asked the question quoted above in a 1927 interview he gave in New York. Prokofiev’s tongue-in-cheek response was more accurate than he intended, however, particularly with regard to his own music and how it was received by American audiences.

Prokofiev composed in a patchwork style, jotting down fragments of themes in a notebook as they came to him. Prokofiev kept these musical diaries for years, and often referred to them when he composed. Several of Prokofiev’s musical ideas for the Third Piano Concerto had been gestating since 1913, including the delicate melody that forms the basis for the Andantino theme and variations. Like a quilt design fashioned from many unrelated patches, Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto is an artful arrangement of musical ideas that evolve into a unified sound collage. Prokofiev put the finishing touches on the third concerto during the summer of 1921, while he was living in St. Brevin-les-Pins, on the northwest coast of France.

The Andante-Allegro contrasts the languid opening clarinet melody with the piano’s ebullient energy. The final theme, a rapidly ascending stampede of thirds in the piano, was one of the first fragments Prokofiev wrote almost a decade earlier. The theme of the Tema con variazioni (Theme with variations) is a lilting, rhythmic melody first heard in the winds; the five variations that follow are, by turns, wistfully elegant, agitated, stormy, mysterious, and frenzied. Prokofiev characterized the Allegro ma non troppo as an “argument” between piano and orchestra, full of “caustic humor … with frequent differences of opinion as regards key.” After much musical bickering, the concerto ends with a blazing coda.

The exuberant, brash Piano Concerto No. 3 drew thunderous applause from American audiences but rather tepid reviews. After the premiere, one Chicago paper described it as “a plum pudding without the plums.” Later concerts in New York produced similar reactions; Prokofiev’s observation about the “certain logic” of contemporary composers proved prescient. Three years after the end of WWI, which disrupted all societal and cultural conventions, audiences were receptive to Prokofiev’s post-war explorations of new sonorities, but critics, often more conservative than their readers, were not. Discouraged by the lackluster American reviews of his music, Prokofiev departed for Europe. In 1932, he made his first recording, playing the Third Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra. This recording helped make the Third Piano Concerto one of Prokofiev’s most popular works.

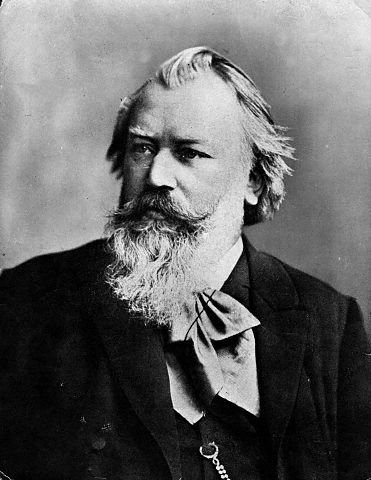

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Composer: born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Work composed: Brahms began working on his first symphony in 1856 and returned to it periodically over the next 19 years. He wrote the bulk of the music between 1874 and 1876.

World premiere: Otto Dessoff led the Badische Staatskapelle in Karlsruhe, on November 4, 1876.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Estimated duration: 42 minutes

““There are fewer things heavier than the burden of a great potential.” ”

In 1853, Robert Schumann wrote a laudatory article about an unknown 20-year-old composer from Hamburg named Johannes Brahms, whom, Schumann declared, was the heir to Beethoven’s musical legacy. Schumann wrote, “If [Brahms] directs his magic wand where the massed power in chorus and orchestra might lend him their strength, we can look forward to even more wondrous glimpses into the secret world of the spirits.” At the time Schumann’s piece was published, Brahms had composed several chamber pieces and works for piano, but nothing for orchestra. The article brought Brahms to the attention of the musical world, but it also dropped a crushing weight of expectation onto his young shoulders. “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it feels to hear behind you the tramp of a giant like Beethoven,” Brahms grumbled.

Because Brahms took almost 20 years to complete what became his Op. 68, one might suppose its long gestation stemmed from Brahms’ possible trepidation about producing a symphony worthy of the Beethovenian ideal. This assumption, on its own, does Brahms a disservice. Daunting though the task might have been, Brahms also wanted to take his time. This measured approach reflects the high regard Brahms had for the symphony as a genre. “Writing a symphony is no laughing matter,” he remarked.

Brahms began sketching the first movement when he was 23, but soon realized he was handicapped by his lack of experience composing for an orchestra. Over the next 19 years, as he continued working on Op. 68, Brahms wrote several other orchestral works, including the 1868 German Requiem and the popular 1873 Variations on a Theme by Haydn (aka the St. Anthony Variations). The enthusiastic response that greeted both works bolstered Brahms’ confidence in his ability to handle orchestral writing. In 1872, Brahms was offered the conductor’s post at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music). This opportunity to work directly with an orchestra gave Brahms the invaluable first-hand experience he needed. 23 years after Schumann’s article first appeared, Brahms premiered his Symphony No. 1 in C minor. It was worth the wait.

Brahms’ friend, the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick, summed up the feelings of many: “Seldom, if ever, has the entire musical world awaited a composer’s first symphony with such tense anticipation … The new symphony is so earnest and complex, so utterly unconcerned with common effects, that it hardly lends itself to quick understanding … [but] even the layman will immediately recognize it as one of the most distinctive and magnificent works of the symphonic literature.”

Hanslick’s reference to the symphony’s complexity was a polite way of saying the music was too serious to appeal to the average listener, but Brahms was unconcerned; he was not trying to woo the public with pretty sounds. “My symphony is long and not exactly lovable,” he acknowledged. The symphony is carefully crafted; one can hear Brahms’ compositional thought processes throughout, especially his decision to incorporate several overt references to Beethoven. The moody, portentous atmosphere of the first movement, and the short thematic fragments from which Brahms spins out seemingly endless developments, are all hallmarks of Beethoven’s style. Brahms also references Beethoven by choosing the key of C minor, which is closely associated with several of Beethoven’s major works, including the Fifth Symphony, Egmont Overture, and Piano Concerto No. 3. And yet, despite all these deliberate nods to Beethoven, this symphony is not, as conductor Hans von Bülow dubbed it, “Beethoven’s Tenth.” The voice is distinctly Brahms’, especially in the inner movements.

The tender, wistful Andante sostenuto contrasts the brooding power of the first movement. Brahms weaves a series of dialogues among different sections of the orchestra, and concludes with a duet for solo violin and horn. In the Allegretto, Brahms slows down Beethoven’s frantic scherzo tempos. The pace is relaxed, easy, featuring lilting themes for strings and woodwinds. The finale’s strong, confident horn solo proclaims Brahms’ victory over the doubts that beset him during Op. 68’s long incubation. Here Brahms also pays his most direct homage to Beethoven, with a majestic theme, first heard in the strings, that closely resembles the “Ode to Joy” melody from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When a listener remarked on this similarity, Brahms snapped irritably, “Any jackass could see that!”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

April 1 & 2, 2022 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Meyer conducts Prokofiev & Brahms

Friday, April 1, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, April 2, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Program

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960)

Sidereus (2010)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 26

Alexander Korsantia, piano

I. Andante– Allegro

II. Tema con variazioni

III. Allegro, ma non troppo

INTERMISSION

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 (1876)

I. Un poco sostenuto— Allegro – Meno allegro

II. Andante sostenuto

III. Un Poco Allegretto e Grazioso

IV. Adagio — Più andante — Allegro non troppo, ma con brio – Più allegro

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “PIANO” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Korngold & Dvorak

March 4 & 5, 2022 at 7:30 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

READ OUR PROGRAM NOTES →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Korngold & Dvorak

Friday, March 4, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, March 4, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Program

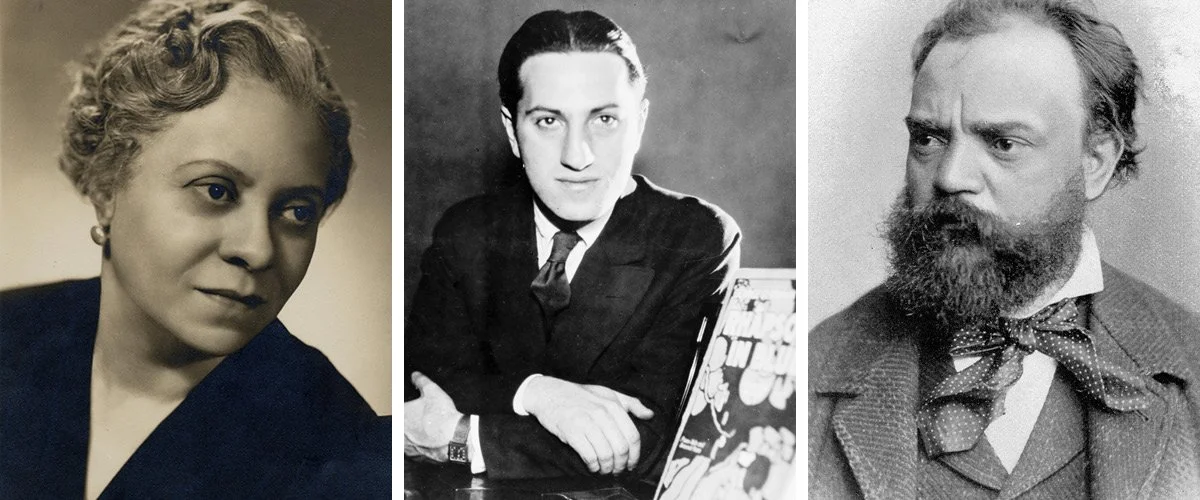

George Walker (1922-2018)

Lyric for Strings (1946)

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

Concerto in D Major for Violin, op. 35 (1945)

Charles Yang, violin

I.Moderato nobile

II. Romance: Andante

III. Allegro assai vivace

INTERMISSION

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Symphony No.8 in G major, Op. 88 (1889)

I.Allegro con brio

II. Adagio

III. Allegretto grazioso

IV. Allegro ma non troppo

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “VIOLIN” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Program Notes: Korngold & Dvorak

Notes about:

George Walker’s Lyric for Strings

Erich Korngold’s Concerto in D major for Violin

Antonin Dvorak’s Symphony No. 8

Program Notes for Korngold & Dvorak

George Walker

Lyric for Strings

Composer: b. June 22, 1922, Washington, D.C.; died August 23, 2018, Montclair, NJ

Work composed: 1946. Dedicated “to my grandmother.”

World premiere: 1946. Seymour Lipkin led a student orchestra from the Curtis Institute of Music in a radio concert.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

For most of a century, despite the systemic pervasive racism he encountered, George Theophilus Walker sustained three successful careers in performance, composition, and teaching. After graduating from Oberlin Conservatory, Walker attended the Curtis Institute, becoming the first Black student to earn an Artist’s Diploma in piano and composition. At Curtis, Walker studied piano with Rudolf Serkin and composition with Gian Carlo Menotti. Walker continued his education at the Eastman School of Music, where he earned a D.M.A. in composition, the first Black composer to do so. In the 1950s, Walker traveled to Paris to study composition with the influential composition teacher Nadia Boulanger.

Walker’s life list of accomplishments includes many more “firsts:” he was the first Black instrumentalist to play a recital in New York’s Town Hall; the first Black soloist to perform with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy, and the first Black instrumentalist to obtain major concert management, with National Concert Artists. In 1996, Walker became the first Black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his Lilacs for Voice and Orchestra, a setting of Walt Whitman’s poem, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In 2000, Walker was elected to the American Classical Music Hall of Fame, the first living composer so honored.

Like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, Walker’s Lyric for Strings – initially titled Lament for Strings – began as a movement for string quartet. Walker wrote his String Quartet No. 1 in 1946 as a graduate student at the Curtis Institute. He dedicated the Lament to his grandmother, who had died the previous year. The quartet premiered on a live radio performance of Curtis’ student orchestra in 1946, and the following year received its concert premiere at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Walker subsequently gave the second movement a new title, Lyric for Strings, and as a stand-alone piece, it quickly became one of the most regularly programmed works by a living composer. Melodies interweave among the instruments, and the pensive atmosphere reflects both the composer’s anguish at the passing of his beloved grandmother, as well as the joy her memory evokes. The serene melodies and lush harmonic underpinnings suggest an expressive but never mawkish sense of love and loss.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

Composer: born May 29, 1897, Vienna; died November 29, 1957, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: 1937-1945. Commissioned by violinist Bronisław Huberman. Dedicated to Gustav Mahler’s widow, Alma Mahler-Werfel.

World premiere: February 15, 1947. Vladimir Golschmann led the St. Louis Symphony with Jascha Heifetz as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons (1 doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, vibraphone, xylophone, celesta, harp, and strings.

Estimated duration: 24 minutes

Erich Korngold was a man out of time. Had he been born a century earlier, his romantic sensibilities would have aligned perfectly with the musical and artistic aesthetics of the 19th century. Instead, Korngold grew up in the tumult of the early 20th century, when his tonal, lyrical style had been eclipsed by the horrors of WWI and the stark modernist trends promulgated by fellow Viennese composers Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern.

Korngold’s prodigious compositional talent emerged early. At age ten, he performed his cantata Gold for Gustav Mahler, whereupon the older composer called him “a genius.” When Korngold was 13, just after his bar mitzvah, the Austrian Imperial Ballet staged his pantomime The Snowman. In his teens, Korngold received commissions from the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; pianist Artur Schnabel performed Korngold’s Op. 2 Piano Sonata on tour, and Korngold also began writing operas, completing two full-scale works by age eighteen. At 23, Korngold’s opera Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) brought him international renown; it was performed in 83 different opera houses.

But by the 1920s, composers had fully embraced modernism. The music of Korngold’s contemporaries bristled with dissonance, unexpected rhythms, and often little that resembled a recognizable melody. Korngold’s music reflected an earlier, bygone era, and his unabashed Romanticism was dismissed as hopelessly out of date. Fortunately for Korngold, around this same time a new forum for his lush expressiveness emerged: film scores. In 1934, director Max Reinhardt invited Korngold to write a score for his film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Korngold subsequently moved to Hollywood, where he spent the next dozen years composing scores for 18 films, including his Oscar-winning music for Anthony Adverse (1936), and The Adventures of Robin Hood starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Claude Rains (1938).

While some composers and critics, then as now, regard film music as less significant than works written for the concert hall, Korngold did not. “I have never drawn a distinction between music for films and for operas or concerts,” he stated, and his violin concerto bears this out. The concerto is a compilation of themes from several Korngold scores, including Another Dawn (1937), Juárez (1939), Anthony Adverse, and The Prince and the Pauper (1937). Korngold’s Violin Concerto has been a favorite of both violinists and audiences everywhere since its premiere, although the New York Sun famously dismissed it as “more corn than gold.”

It was a running joke in the Korngold family that every time their family friend Bronisław Huberman saw Korngold, the Polish violinist would demand, “Erich! Where’s my concerto?” At dinner one evening in Korngold’s house in Los Angeles, Korngold responded to Huberman’s mock-serious question by going to his piano and playing the theme from Another Dawn. Huberman exclaimed, “That’s it! That will be my concerto. Promise me you’ll write it.” Korngold complied, but it was Jascha Heifetz, another child prodigy, who gave the first performance. In the program notes for the premiere, Korngold wrote, “In spite of its demand for virtuosity in the finale, the work with its many melodic and lyric episodes was contemplated rather for a Caruso of the violin than for a Paganini. It is needless to say how delighted I am to have my concerto performed by Caruso and Paganini in one person: Jascha Heifetz.”

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88 [aka No. 4]

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: Dvořák wrote the Symphony No. 8 between August 26 and November 8, 1889, at his country home, Vysoká, in Bohemia. The score was dedicated “To the Bohemian Academy of Emperor Franz Joseph for the Encouragement of Arts and Literature, in thanks for my election [to the Prague Academy].”

World premiere: Dvořák conducted the first performance in Prague on February 2, 1890.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani ,and strings.

Estimated duration: 36 minutes

From its inception, Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony in G major was more than a composition; in musical terms it represented everything that made Dvořák a proud Bohemian. Trouble started when Dvořák’s German publisher, Fritz Simrock, wanted to publish the symphony’s movement titles and Dvořák’s name in German translation. This might seem like an unimportant detail over which to haggle, but for Dvořák it was a matter of cultural life and death. Since the age of 26, Dvořák had been a reluctant citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty. Under the Hapsburgs, Czech language and culture were vigorously repressed. Dvořák, an ardent Czech patriot who resented the Germanic norms mandated by the Empire, categorically refused Simrock’s request.

For his part, Simrock was not especially enthusiastic about publishing Dvořák’s symphonies, which didn’t sell as well as Dvořák’s Slavonic dances and piano music. Simrock and Dvořák also haggled over the composer’s fee; Simrock had paid 3,000 marks for Dvořák’s Symphony No. 7, but inexplicably and insultingly offered only 1,000 for the Eighth Symphony. Outraged, Dvořák offered his Symphony No. 8 to the London firm Novello, which published it in 1890.

The G Major symphony broke new ground from the moment of its premiere. Op. 88 was, as the composer explained, meant to be “different from the other symphonies, with individual thoughts worked out in a new way.” This “new way” refers to Dvořák’s musical transformation of the Czech countryside he loved into a unique sonic landscape. Within the music, Dvořák included sounds from nature, particularly hunting horn calls and birdsongs played by various wind instruments. Biographer Hanz-Hubert Schönzeler observed, “When one walks in those forests surrounding Dvořák’s country home on a sunny summer’s day, with the birds singing and the leaves of trees rustling in a gentle breeze, one can virtually hear the music.”

Serenity floats over the Adagio. As in the first movement, Dvořák plays with tonality; E-flat major slides into its darker counterpart, C minor. Dvořák was most at home in rural settings, and the music of this Adagio evokes the tranquil landscape of the garden at Vysoká, Dvořák’s country home. In a manner similar to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, the music suggests an idyllic summer’s day interrupted by a cloudburst, after which the sun reappears, striking sparkles from the raindrops.

During a rehearsal of the trumpet fanfare in the last movement, conductor Rafael Kubelik declared, “Gentlemen, in Bohemia the trumpets never call to battle – they always call to the dance!” After this opening summons, cellos sound the main theme. Quieter variations on the cello melody feature solo flute and strings, and the symphony ends with an exuberant brassy blast.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Gier conducts Márquez & Shostakovich

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Gier conducts Márquez & Shostakovich

Friday, January 7, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, January 8, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Gallo Center for the Arts, Mary Stuart Rogers Theater

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “CELLO” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 21, 2021 at 8 pm

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Candlelight Concert

Tuesday, December 21, 2021

Doors Open at 7 pm

Concert Starts at 8 pm

St. Stanislaus Catholic Church

1200 Maze Boulevard, Modesto

Program

“Sinfony” from Messiah by George Frideric Handel

O Come, O Come, Emmanuel arranged by Alen Lohr

A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28 by Benjamin Britten

I. Hodie Christus natus est

There Is No Rose by Rene Clausen

“Pifa” from Messiah by George Frideric Handel

O Little Town of Bethlehem arranged by Tom Kennedy

Pat-a-Pan arranged by Matthew Compton

Twas in the Moon of Wintertime arranged by Matthew Prins

Gloria by Antonio Vivaldi

I. Gloria in excelsis Deo

II. Et in terra pax hominibus

III. Laudamus te

IV. Gratias agimus tibi

VI. Domine Fili unigenite

VII. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

VIII. Qui tollis peccata mundi

X. Quoniam tu solus sanctus

XI. Cum Sancto Spiritu

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing arranged by Ian Good

Silent Night arranged by Tom Kennedy

“Hallelujah” from Messiah by George Frideric Handel

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “CANDLELIGHT” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

Holiday Pops!

December 3, 2021 at 7:30 pm

December 4, 2021 at 2 pm

VISIT MOBILE PROGRAM →

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE VERSION →

Modesto Symphony Orchestra

Holiday Pops!

Friday, December 3 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, December 4 at 2 pm

Mary Stuart Rogers Theater, Gallo Center for the Arts

Program

Holiday Overture

by James M. Stephenson, III

It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year

arranged by Jim Kessler

I Saw Three Ships/Jeanette, Isabella

arranged by James M. Stephenson, III

Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas

arranged by Jim Kessler

We Need A Little Christmas

by Jerry Herman; arranged by Jim Kessler

O Come, All Ye Faithful

by Frederick Oakeley and John F. Wade; arranged by Doug Andrews

In the Bleak Midwinter

arranged by James M. Stephenson, III

Sleigh Ride

by Leroy Anderson

Think of Me

by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Charles Hart

Intermission -

A Charleston Christmas

arranged by James M. Stephenson, III

Christmas Eve/Sarajevo 12/24

by Paul O’Neill and Robert Kinkel; arranged by Bob Phillips

Silent Night Medley

arranged by Jim Kessler

The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)

by Mel Torme and Robert Wells; arranged by James M. Stephenson, III

Riu, riu, chiu

attributed to Mateo Flecha the Elder

There Is No Rose

by René Clausen

The Night Before Christmas

by Randol Alan Bass

O Holy Night!

arranged and orchestrated by David T. Clydesdale

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “HOLIDAY” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this weekend’s performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.

About this Performance

MSYO Season Opening Concert

November 13, 2021 at 2 pm

Modesto Symphony Youth Orchestra

Season Opening Concert

November 13, 2021 at 2pm

Mary Stuart Rogers Theater, Gallo Center for the Arts

Program

Concert Orchestra

Donald C. Grishaw, conductor

Two Handel Marches

George Frideric Handel, arr. Merle J. Isaac

Highlights from Harry Potter

John Williams, arr. Michael Story

“Anvil Chorus” from Il Trovatore

Giuseppe Verdi, arr. Sandra Dackow

Overture from Orpheus in the Underworld

Jacques Offenbach, ed. Clark McAlister

Symphony Orchestra

Wayland Whitney, conductor

Overture from Zampa

J. Ferdinand Herold, ad. Henry Sopkin

Emperor Waltzes, Op. 437

Johann Strauss

L’Arlesienne Suite No. 2

I. Pastorale

III. Minuet

IV. Farandole

Georges Bizet, arr. Fritz Hoffmann

Join Mobile MSO!

Text “MSYO” to (209) 780-0424

to receive a link to the concert program & text message updates prior to this weekend’s performance!

By texting to this number, you may receive messages that pertain to the Modesto Symphony Orchestra and its performances. msg&data rates may apply. Reply HELP for help, STOP to cancel.