Program Notes: Rhapsody in Blue

Notes about:

Price’s Concert Overture No. 2

Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 in E minor, “From the New World,” Op. 95

Program Notes for October 21 & 22, 2022

Rhapsody in Blue

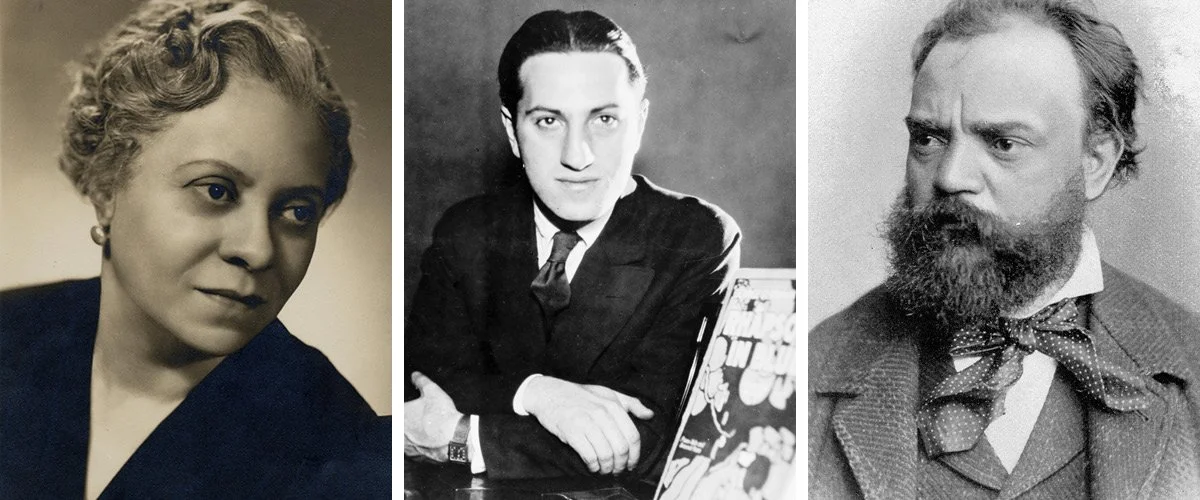

Florence Price

Concert Overture No. 2

Composer: born April 9, 1887, Little Rock, AR; died June 3, 1953, Chicago

Work composed: 1943

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: piccolo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, harp, and strings

Estimated duration:15 minutes

As the first Black female American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra, Florence Price enjoyed considerable renown during her lifetime. Her compositional skill and fame notwithstanding, the entrenched institutional racism and sexism of the white male classical music establishment effectively erased Price and her music from general awareness for decades after her death. In 2009, a large collection of scores and unpublished works by Price were discovered in a house in rural Illinois. Since then, scholars, musicians, and audiences have been discovering Price’s work and her rich legacy.

The daughter of a musical mother, Price was a prodigy, giving her first recital at age four and publishing her first composition at 11. During her childhood and teens, Price’s mother was the guiding force behind her piano and composition studies. Young Florence entered New England Conservatory in 1903, at 16, where she double majored in organ performance and piano pedagogy. While at NEC, Price also studied composition with George Whitefield Chadwick. Chadwick was an early champion of women as composers, which was highly unusual at the time, and he believed that American composers should incorporate the rich traditions of native American and “Negro” styles in their own works. Price, already inclined in this direction, was encouraged by Chadwick, and many of her works, including tonight’s Concert Overture No. 2, reflect the expressive and distinctive sounds of Negro traditions, particularly the spirituals, ragtime, and folkdance rhythms whose origins trace back to Africa. This overture features the spirituals “Go Down, Moses,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “Every Time I Feel the Spirit.”

George Gershwin

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: Gershwin wrote Rhapsody in Blue in the first three weeks of 1924

World premiere: Gershwin was at the piano when Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra premiered Rhapsody in Blue at Aeolian Hall in New York City, on February 12, 1924

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, gong, glockenspiel, snare drum, celesta, triangle, banjo, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

Rhapsody in Blue introduced jazz to classical audiences, and simultaneously made an instant star of its composer. From its iconic clarinet glissando to its brilliant finale, Rhapsody in Blue epitomizes the Gershwin sound, and transformed the 25-year-old Tin Pan Alley songwriter into a composer of “serious” music.

On January 4, 1924, Ira Gershwin showed George a news report in the New York Tribune about a concert put together by jazz bandleader Paul Whiteman, grandiosely titled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” that would endeavor to trace the history of jazz. The article concluded, “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto.” This was certainly news to Gershwin, who was then in rehearsals for a Broadway show, Sweet Little Devil. Gershwin contacted Whiteman to refute the Tribune article, but Whiteman eventually talked Gershwin into writing the concerto.

In 1931, Gershwin described to biographer Isaac Goldberg how the musical ideas for Rhapsody in Blue first emerged: “It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer … And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper – the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end … I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

At the premiere, Gershwin’s unique realization of this “musical kaleidoscope of America,” coupled with his phenomenal abilities at the keyboard, wowed the audience as much as the novelty of hearing jazz idioms in a classical work.

The opening clarinet solo got its signature jazzy glissando from Whiteman’s clarinetist Ross Gorman. This opening unleashes a floodgate of colorful ideas that blend seamlessly. The pulsing syncopated rhythms and showy music eventually morph into a warm, expansive melody à la Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: 1892-1893 in New York City

World premiere: Anton Seidl led the New York Philharmonic on December 16, 1893, at Carnegie Hall.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 40 minutes

Antonín Dvořák began his Ninth Symphony in December 1892, shortly after he arrived in America, and completed it the following May. During his three-year sojourn in New York, Dvořák explored the city, watched trains and large ships arrive and depart, fed pigeons in Central Park, and met all kinds of people. Late in 1892, Dvořák wrote to a friend back home, “The Americans expect great things of me. I am to show them the way into the Promised Land, the realm of a new, independent art, in short, a national style of music! … This will certainly be a great and lofty task, and I hope that with God’s help I shall succeed in it. I have plenty of encouragement to do so.”

Dvořák was also introduced to a great deal of American folk music, including Native American melodies and Negro spirituals. However, he did not quote any of them in the Ninth Symphony. Dvořák explained, “The influence of America can be readily felt by anyone with ‘a nose.’” That is, hints of the uniquely American flavor of this music are discernable throughout, as Dvořák made use of the syncopated rhythms, repeated patterns, and particular scales common to much of America’s indigenous music. But the Ninth Symphony is not a patchwork of previously existing materials, and all the melodies in the Ninth Symphony are Dvořák’s own (including the famous English horn solo in the Largo, which was later given the title “Goin’ Home,” with accompanying text, by one of Dvořák’s New York composition students, a young Black composer and baritone named Harry Burleigh).

“I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of Indian music, and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, harmony, counterpoint, and orchestral color,” Dvořák explained. As for the title, “From the New World,” Dvořák intended it as an aural picture postcard to be mailed back to friends and family in Europe and meant simply “Impressions and Greetings from the New World.”

At the premiere, the audience applauded every movement with great enthusiasm, especially the Largo, which they cheered without pause until Dvořák rose from his seat and took a bow. A critic writing for the New York Evening Post spoke for most when he wrote, “Anyone who heard it could not deny that it is the greatest symphonic work ever composed in this country … A masterwork has been added to the symphonic literature.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Korngold & Dvorak

Notes about:

George Walker’s Lyric for Strings

Erich Korngold’s Concerto in D major for Violin

Antonin Dvorak’s Symphony No. 8

Program Notes for Korngold & Dvorak

George Walker

Lyric for Strings

Composer: b. June 22, 1922, Washington, D.C.; died August 23, 2018, Montclair, NJ

Work composed: 1946. Dedicated “to my grandmother.”

World premiere: 1946. Seymour Lipkin led a student orchestra from the Curtis Institute of Music in a radio concert.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 6 minutes

For most of a century, despite the systemic pervasive racism he encountered, George Theophilus Walker sustained three successful careers in performance, composition, and teaching. After graduating from Oberlin Conservatory, Walker attended the Curtis Institute, becoming the first Black student to earn an Artist’s Diploma in piano and composition. At Curtis, Walker studied piano with Rudolf Serkin and composition with Gian Carlo Menotti. Walker continued his education at the Eastman School of Music, where he earned a D.M.A. in composition, the first Black composer to do so. In the 1950s, Walker traveled to Paris to study composition with the influential composition teacher Nadia Boulanger.

Walker’s life list of accomplishments includes many more “firsts:” he was the first Black instrumentalist to play a recital in New York’s Town Hall; the first Black soloist to perform with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy, and the first Black instrumentalist to obtain major concert management, with National Concert Artists. In 1996, Walker became the first Black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his Lilacs for Voice and Orchestra, a setting of Walt Whitman’s poem, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In 2000, Walker was elected to the American Classical Music Hall of Fame, the first living composer so honored.

Like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, Walker’s Lyric for Strings – initially titled Lament for Strings – began as a movement for string quartet. Walker wrote his String Quartet No. 1 in 1946 as a graduate student at the Curtis Institute. He dedicated the Lament to his grandmother, who had died the previous year. The quartet premiered on a live radio performance of Curtis’ student orchestra in 1946, and the following year received its concert premiere at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Walker subsequently gave the second movement a new title, Lyric for Strings, and as a stand-alone piece, it quickly became one of the most regularly programmed works by a living composer. Melodies interweave among the instruments, and the pensive atmosphere reflects both the composer’s anguish at the passing of his beloved grandmother, as well as the joy her memory evokes. The serene melodies and lush harmonic underpinnings suggest an expressive but never mawkish sense of love and loss.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

Composer: born May 29, 1897, Vienna; died November 29, 1957, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: 1937-1945. Commissioned by violinist Bronisław Huberman. Dedicated to Gustav Mahler’s widow, Alma Mahler-Werfel.

World premiere: February 15, 1947. Vladimir Golschmann led the St. Louis Symphony with Jascha Heifetz as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons (1 doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, vibraphone, xylophone, celesta, harp, and strings.

Estimated duration: 24 minutes

Erich Korngold was a man out of time. Had he been born a century earlier, his romantic sensibilities would have aligned perfectly with the musical and artistic aesthetics of the 19th century. Instead, Korngold grew up in the tumult of the early 20th century, when his tonal, lyrical style had been eclipsed by the horrors of WWI and the stark modernist trends promulgated by fellow Viennese composers Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern.

Korngold’s prodigious compositional talent emerged early. At age ten, he performed his cantata Gold for Gustav Mahler, whereupon the older composer called him “a genius.” When Korngold was 13, just after his bar mitzvah, the Austrian Imperial Ballet staged his pantomime The Snowman. In his teens, Korngold received commissions from the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; pianist Artur Schnabel performed Korngold’s Op. 2 Piano Sonata on tour, and Korngold also began writing operas, completing two full-scale works by age eighteen. At 23, Korngold’s opera Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) brought him international renown; it was performed in 83 different opera houses.

But by the 1920s, composers had fully embraced modernism. The music of Korngold’s contemporaries bristled with dissonance, unexpected rhythms, and often little that resembled a recognizable melody. Korngold’s music reflected an earlier, bygone era, and his unabashed Romanticism was dismissed as hopelessly out of date. Fortunately for Korngold, around this same time a new forum for his lush expressiveness emerged: film scores. In 1934, director Max Reinhardt invited Korngold to write a score for his film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Korngold subsequently moved to Hollywood, where he spent the next dozen years composing scores for 18 films, including his Oscar-winning music for Anthony Adverse (1936), and The Adventures of Robin Hood starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Claude Rains (1938).

While some composers and critics, then as now, regard film music as less significant than works written for the concert hall, Korngold did not. “I have never drawn a distinction between music for films and for operas or concerts,” he stated, and his violin concerto bears this out. The concerto is a compilation of themes from several Korngold scores, including Another Dawn (1937), Juárez (1939), Anthony Adverse, and The Prince and the Pauper (1937). Korngold’s Violin Concerto has been a favorite of both violinists and audiences everywhere since its premiere, although the New York Sun famously dismissed it as “more corn than gold.”

It was a running joke in the Korngold family that every time their family friend Bronisław Huberman saw Korngold, the Polish violinist would demand, “Erich! Where’s my concerto?” At dinner one evening in Korngold’s house in Los Angeles, Korngold responded to Huberman’s mock-serious question by going to his piano and playing the theme from Another Dawn. Huberman exclaimed, “That’s it! That will be my concerto. Promise me you’ll write it.” Korngold complied, but it was Jascha Heifetz, another child prodigy, who gave the first performance. In the program notes for the premiere, Korngold wrote, “In spite of its demand for virtuosity in the finale, the work with its many melodic and lyric episodes was contemplated rather for a Caruso of the violin than for a Paganini. It is needless to say how delighted I am to have my concerto performed by Caruso and Paganini in one person: Jascha Heifetz.”

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88 [aka No. 4]

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: Dvořák wrote the Symphony No. 8 between August 26 and November 8, 1889, at his country home, Vysoká, in Bohemia. The score was dedicated “To the Bohemian Academy of Emperor Franz Joseph for the Encouragement of Arts and Literature, in thanks for my election [to the Prague Academy].”

World premiere: Dvořák conducted the first performance in Prague on February 2, 1890.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani ,and strings.

Estimated duration: 36 minutes

From its inception, Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony in G major was more than a composition; in musical terms it represented everything that made Dvořák a proud Bohemian. Trouble started when Dvořák’s German publisher, Fritz Simrock, wanted to publish the symphony’s movement titles and Dvořák’s name in German translation. This might seem like an unimportant detail over which to haggle, but for Dvořák it was a matter of cultural life and death. Since the age of 26, Dvořák had been a reluctant citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty. Under the Hapsburgs, Czech language and culture were vigorously repressed. Dvořák, an ardent Czech patriot who resented the Germanic norms mandated by the Empire, categorically refused Simrock’s request.

For his part, Simrock was not especially enthusiastic about publishing Dvořák’s symphonies, which didn’t sell as well as Dvořák’s Slavonic dances and piano music. Simrock and Dvořák also haggled over the composer’s fee; Simrock had paid 3,000 marks for Dvořák’s Symphony No. 7, but inexplicably and insultingly offered only 1,000 for the Eighth Symphony. Outraged, Dvořák offered his Symphony No. 8 to the London firm Novello, which published it in 1890.

The G Major symphony broke new ground from the moment of its premiere. Op. 88 was, as the composer explained, meant to be “different from the other symphonies, with individual thoughts worked out in a new way.” This “new way” refers to Dvořák’s musical transformation of the Czech countryside he loved into a unique sonic landscape. Within the music, Dvořák included sounds from nature, particularly hunting horn calls and birdsongs played by various wind instruments. Biographer Hanz-Hubert Schönzeler observed, “When one walks in those forests surrounding Dvořák’s country home on a sunny summer’s day, with the birds singing and the leaves of trees rustling in a gentle breeze, one can virtually hear the music.”

Serenity floats over the Adagio. As in the first movement, Dvořák plays with tonality; E-flat major slides into its darker counterpart, C minor. Dvořák was most at home in rural settings, and the music of this Adagio evokes the tranquil landscape of the garden at Vysoká, Dvořák’s country home. In a manner similar to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, the music suggests an idyllic summer’s day interrupted by a cloudburst, after which the sun reappears, striking sparkles from the raindrops.

During a rehearsal of the trumpet fanfare in the last movement, conductor Rafael Kubelik declared, “Gentlemen, in Bohemia the trumpets never call to battle – they always call to the dance!” After this opening summons, cellos sound the main theme. Quieter variations on the cello melody feature solo flute and strings, and the symphony ends with an exuberant brassy blast.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com