Program Notes: Rhapsody in Blue

Notes about:

Price’s Concert Overture No. 2

Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 in E minor, “From the New World,” Op. 95

Program Notes for October 21 & 22, 2022

Rhapsody in Blue

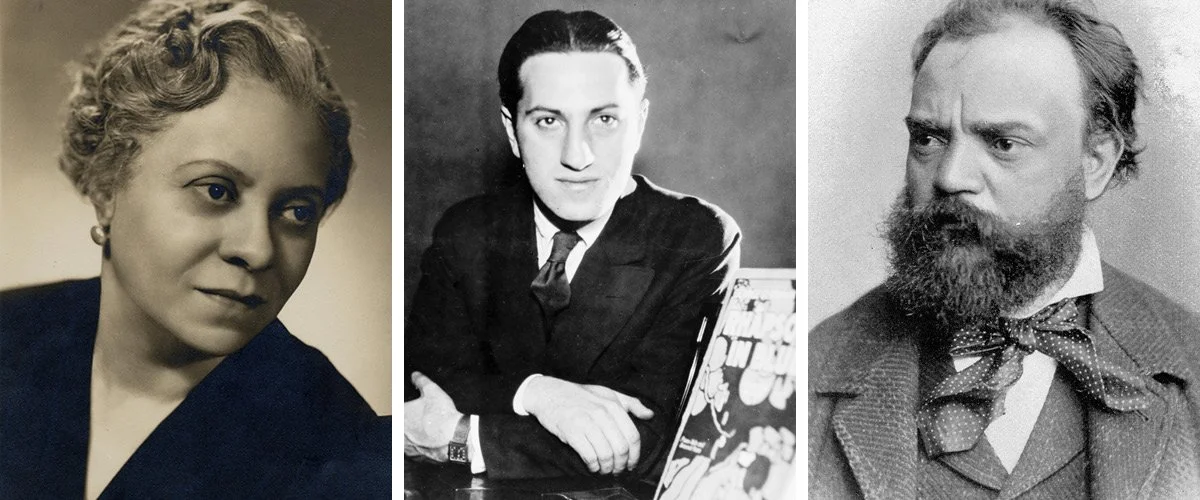

Florence Price

Concert Overture No. 2

Composer: born April 9, 1887, Little Rock, AR; died June 3, 1953, Chicago

Work composed: 1943

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: piccolo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, harp, and strings

Estimated duration:15 minutes

As the first Black female American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra, Florence Price enjoyed considerable renown during her lifetime. Her compositional skill and fame notwithstanding, the entrenched institutional racism and sexism of the white male classical music establishment effectively erased Price and her music from general awareness for decades after her death. In 2009, a large collection of scores and unpublished works by Price were discovered in a house in rural Illinois. Since then, scholars, musicians, and audiences have been discovering Price’s work and her rich legacy.

The daughter of a musical mother, Price was a prodigy, giving her first recital at age four and publishing her first composition at 11. During her childhood and teens, Price’s mother was the guiding force behind her piano and composition studies. Young Florence entered New England Conservatory in 1903, at 16, where she double majored in organ performance and piano pedagogy. While at NEC, Price also studied composition with George Whitefield Chadwick. Chadwick was an early champion of women as composers, which was highly unusual at the time, and he believed that American composers should incorporate the rich traditions of native American and “Negro” styles in their own works. Price, already inclined in this direction, was encouraged by Chadwick, and many of her works, including tonight’s Concert Overture No. 2, reflect the expressive and distinctive sounds of Negro traditions, particularly the spirituals, ragtime, and folkdance rhythms whose origins trace back to Africa. This overture features the spirituals “Go Down, Moses,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “Every Time I Feel the Spirit.”

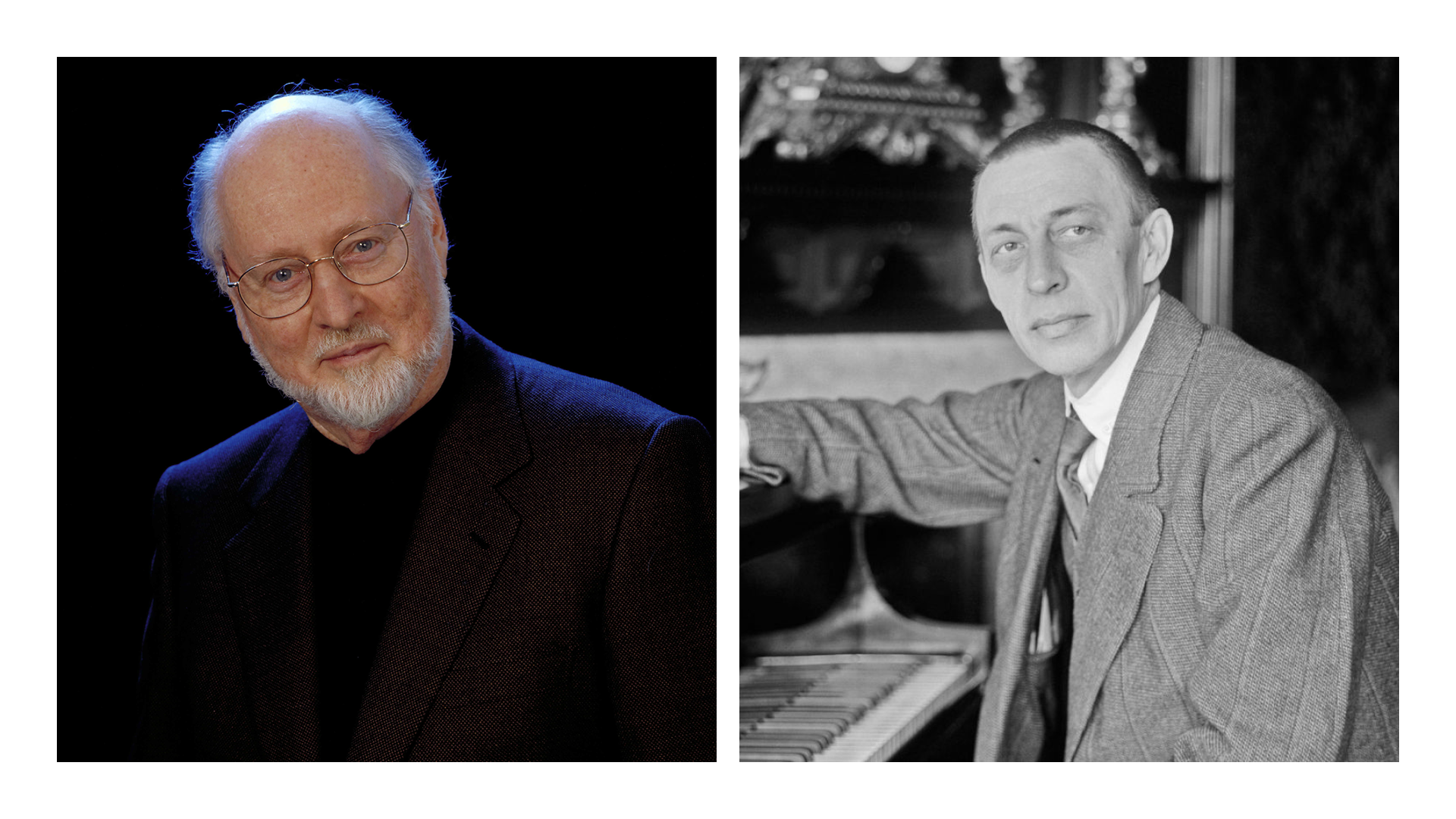

George Gershwin

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: Gershwin wrote Rhapsody in Blue in the first three weeks of 1924

World premiere: Gershwin was at the piano when Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra premiered Rhapsody in Blue at Aeolian Hall in New York City, on February 12, 1924

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, gong, glockenspiel, snare drum, celesta, triangle, banjo, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

Rhapsody in Blue introduced jazz to classical audiences, and simultaneously made an instant star of its composer. From its iconic clarinet glissando to its brilliant finale, Rhapsody in Blue epitomizes the Gershwin sound, and transformed the 25-year-old Tin Pan Alley songwriter into a composer of “serious” music.

On January 4, 1924, Ira Gershwin showed George a news report in the New York Tribune about a concert put together by jazz bandleader Paul Whiteman, grandiosely titled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” that would endeavor to trace the history of jazz. The article concluded, “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto.” This was certainly news to Gershwin, who was then in rehearsals for a Broadway show, Sweet Little Devil. Gershwin contacted Whiteman to refute the Tribune article, but Whiteman eventually talked Gershwin into writing the concerto.

In 1931, Gershwin described to biographer Isaac Goldberg how the musical ideas for Rhapsody in Blue first emerged: “It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer … And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper – the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end … I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

At the premiere, Gershwin’s unique realization of this “musical kaleidoscope of America,” coupled with his phenomenal abilities at the keyboard, wowed the audience as much as the novelty of hearing jazz idioms in a classical work.

The opening clarinet solo got its signature jazzy glissando from Whiteman’s clarinetist Ross Gorman. This opening unleashes a floodgate of colorful ideas that blend seamlessly. The pulsing syncopated rhythms and showy music eventually morph into a warm, expansive melody à la Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: 1892-1893 in New York City

World premiere: Anton Seidl led the New York Philharmonic on December 16, 1893, at Carnegie Hall.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 40 minutes

Antonín Dvořák began his Ninth Symphony in December 1892, shortly after he arrived in America, and completed it the following May. During his three-year sojourn in New York, Dvořák explored the city, watched trains and large ships arrive and depart, fed pigeons in Central Park, and met all kinds of people. Late in 1892, Dvořák wrote to a friend back home, “The Americans expect great things of me. I am to show them the way into the Promised Land, the realm of a new, independent art, in short, a national style of music! … This will certainly be a great and lofty task, and I hope that with God’s help I shall succeed in it. I have plenty of encouragement to do so.”

Dvořák was also introduced to a great deal of American folk music, including Native American melodies and Negro spirituals. However, he did not quote any of them in the Ninth Symphony. Dvořák explained, “The influence of America can be readily felt by anyone with ‘a nose.’” That is, hints of the uniquely American flavor of this music are discernable throughout, as Dvořák made use of the syncopated rhythms, repeated patterns, and particular scales common to much of America’s indigenous music. But the Ninth Symphony is not a patchwork of previously existing materials, and all the melodies in the Ninth Symphony are Dvořák’s own (including the famous English horn solo in the Largo, which was later given the title “Goin’ Home,” with accompanying text, by one of Dvořák’s New York composition students, a young Black composer and baritone named Harry Burleigh).

“I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of Indian music, and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, harmony, counterpoint, and orchestral color,” Dvořák explained. As for the title, “From the New World,” Dvořák intended it as an aural picture postcard to be mailed back to friends and family in Europe and meant simply “Impressions and Greetings from the New World.”

At the premiere, the audience applauded every movement with great enthusiasm, especially the Largo, which they cheered without pause until Dvořák rose from his seat and took a bow. A critic writing for the New York Evening Post spoke for most when he wrote, “Anyone who heard it could not deny that it is the greatest symphonic work ever composed in this country … A masterwork has been added to the symphonic literature.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

Notes about:

Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, op. 62

Wijeratne’s Tabla Concerto

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 in F minor, op. 36

Program Notes for May 6 & 7, 2022

Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

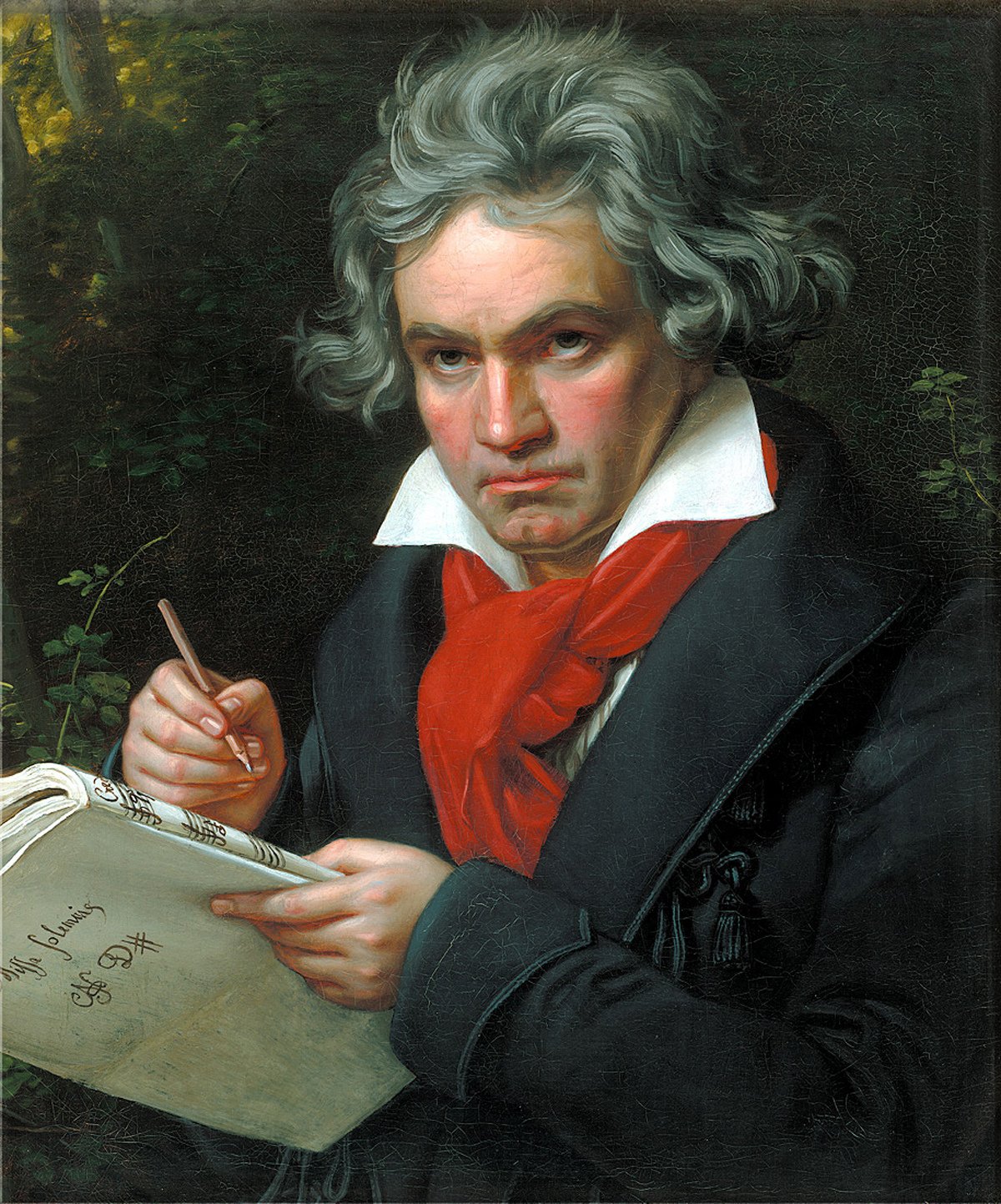

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Coriolan Overture, op. 26

Composer: born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

Work composed: 1807

World premiere: Beethoven conducted a private concert in the Vienna palace of his patron, Prince Lobkowitz, in March 1807, in a performance that also included premieres of his Symphony No. 4 and Piano Concerto No. 4.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Most overtures serve as instrumental introductions to operas or plays. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, although inspired by his countryman Heinrich Joseph Collin’s play about the Roman general Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, was a purely orchestral work from its inception. Unfortunately for Collin, his play, unlike Shakespeare’s on the same subject, was not well received in its initial run in 1804, nor its revival three years later.

In Collin’s play, a hubristic Coriolanus declares war on his hometown of Rome, which had exiled him for his inattention to its plebeian citizens. Enraged, Coriolanus enlists the help of Rome’s most fearsome enemies, the Volsci, to storm the city. As Coriolanus approaches at the head of the Volscian armies, Roman officials sue for peace, to no avail. Coriolanus’ wife, Volumnia, along with his mother and his two sons, also beg him to cease fighting. Coriolanus is moved by his family’s entreaties and, overcome with shame at his dishonorable behavior, literally falls on his sword (this differs from Shakespeare’s ending, in which Coriolanus is murdered).

The dramatic elements of Coriolanus’ story inspired Beethoven’s musical imagination. The music traces an emotional arc, contrasting Coriolanus’ fury and bellicosity with Volumnia’s quiet, forceful pleas for peace.

Dinuk Wijeratne

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born 1978, Sri Lanka

Work composed: 2011, commissioned by Symphony Nova Scotia

World premiere: Recorded live by the CBC, February 9th, 2012 at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium, Halifax, Nova Scotia, featuring Ed Hanley (Tabla) & Symphony Nova Scotia conducted by Bernhard Gueller.

*The Tabla Concerto was twice a finalist for the Masterworks Arts Award (2012, 2016).

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling cor anglais), 2 clarinets in B♭ (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 2 horns in F, 2 trumpets in B, 1 trombone, timpani, 2 percussion, harp, strings

Duration: 27 minutes

Composer’s original program notes:

Canons, Circles

Folk song: ‘White in the moon the long road lies (that leads me from my love)’

Garland of Gems

While the origins of the Tabla are somewhat obscure, it is evident that this ‘king’ of Indian percussion instruments has achieved global popularity for the richness of its timbre, and for the virtuosity of a rhythmically complex repertoire that cannot be separated from the instrument itself. In writing a large-scale work for Tabla and Symphony Orchestra, it is my hope to allow each entity to preserve its own aesthetic. Perhaps, at the same time, the stage will be set for some new discoveries.

While steeped in tradition, the Tabla lends itself heartily to innovation, and has shown its cultural versatility as an increasingly sought-after instrument in contemporary Western contexts such as Pop, Film Music, and World Music Fusion. This notion led me to conceive of an opening movement that would do the not-so-obvious by placing the Tabla first in a decidedly non-Indian context. Here, initiated by a quasi-Baroque canon in four parts, the music quickly turns into an evocation of one my favourite genres of electronic music: ‘Drum-&-Bass’, characterised by rapid ‘breakbeat’ rhythms in the percussion. Of course, there are some North-Indian Classical musical elements present. The whole makes for a rather bizarre stew that reflects globalisation, for better or worse!

A brief second movement becomes a short respite from the energy of the outer movements, and offers a perspective of the Tabla as accompanist in the lyrical world of Indian folk-song. Set in ‘dheepchandhi’, a rhythmic cycle of 14 beats, the gently lilting gait of theTabla rhythm supports various melodic fragments that come together to form an ephemeral love-song.

Typically, a Tabla player concluding a solo recital would do so by presenting a sequence of short, fixed (non-improvised) compositions from his/her repertoire. Each mini-composition, multi-faceted as a little gem, would often be presented first in the form of a vocal recitation. The traditional accompaniment would consist of a drone as well as a looping melody outlining the time cycle – a ‘nagma’ – against which the soloist would weave rhythmically intricate patterns of tension and release. I wanted to offer my own take on a such a recital finale, with the caveat that the orchestra is no bystander. In this movement, it is spurred on by the soloist to share in some of the rhythmic complexity. The whole movement is set in ‘teentaal’, or 16-beat cycle, and in another departure from the traditional norm, my nagma kaleidoscopically changes colour from start to finish. I am indebted to Ed Hanley for helping me choose several ‘gems’ from the Tabla repertoire, although we have certainly had our own fun in tweaking a few, not to mention composing a couple from scratch.

© Dinuk Wijeratne 2011

Notes from the Conductor, Paul Haas:

As a conductor, I’m always on the lookout for great new music. I love that feeling of discovery, especially when I can share it with orchestra musicians and a whole auditorium full of audience members. And Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto is one of the best pieces I’ve ever come across: full of life, emotion, and color.

The first time I ever programmed it (4 years ago in Thunder Bay, Canada) I wanted the Tabla Concerto to end the entire concert, and I needed it to leave the audience ecstatic. There was a stumbling block, though: the third movement (the written ending) of the Tabla Concerto is admittedly wonderful and down-to-earth, and the soloist sings in addition to playing the tablas. But it doesn’t end with that true excitement and momentum I was looking for. From my perspective, it’s almost impossible to end a concert with it, especially if you want the audience so excited they jump out of their seats.

But somehow I knew this was the right piece to close with. So I thought and thought, and eventually it hit me. Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto actually IS the perfect closer, but only if you do the first two movements, and in reverse order. So we started with the second movement, and then we ended with the first movement. And it was sensational. So sensational, in fact, that I begged Dinuk to let me conduct it this way for you, tonight. So that we can end the first half of our evening together with that same feeling of excitement we achieved in Thunder Bay.

Dinuk agreed, and the rest is history. I can’t wait to share his incredible music with you.

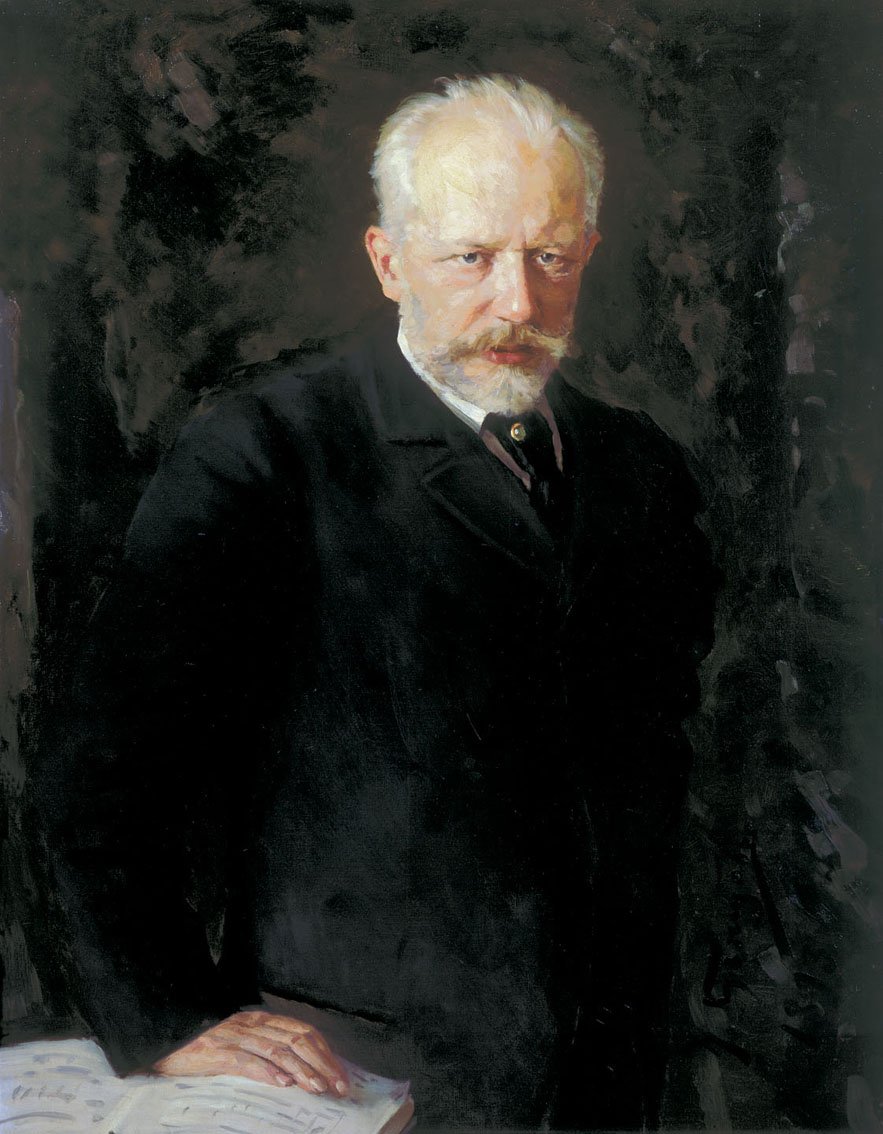

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No.4 in F minor, Op. 36

Composer: born May 7, 1840, Kamsko-Votinsk, Viatka province, Russia; died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg

Work composed: 1877-78. Dedicated to Nadezhda von Meck

World premiere: Nikolai Rubinstein led the Russian Musical Society orchestra on February 22, 1878, in Moscow

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 44 minutes

When a former student from the Moscow Conservatory challenged Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky about the “program” for his fourth symphony, the composer responded, “Of course my symphony is programmatic, but this program is such that it cannot be formulated in words. That would excite ridicule and appear comic … In essence, my symphony is an imitation of Beethoven’s Fifth; i.e., I imitated not the musical ideas, but the fundamental concept.”

In December 1876, Tchaikovsky began an epistolary relationship with Mrs. Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and ardent fan of Tchaikovsky’s music. Mme. von Meck offered to become Tchaikovsky’s patron on the condition that they never meet in person; the introverted Tchaikovsky agreed. Soon after von Meck first wrote to Tchaikovsky, he began the Fourth Symphony. As he worked, Tchaikovsky kept von Meck informed of his progress. He dedicated the Fourth Symphony “to my best friend,” which simultaneously paid tribute to von Meck and insured her privacy.

Six months later, Tchaikovsky encountered Antonina Ivanova Milyukova, a former Conservatory student obsessed with her one-time professor. She sent Tchaikovsky several impassioned letters, which alarmed him; eventually Milyukova threatened to kill herself if Tchaikovsky did not return her affection. This untenable situation, combined with Tchaikovsky’s tortured feelings about his sexual orientation and his desire to silence gossip about it, led to a hasty, ill-advised union. Tchaikovsky fled from Milyukova a month after the wedding (their marriage officially ended after three months, although they were never divorced) and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. He was unable to compose any music for the next three years.

Beginning with the Fourth Symphony, Tchaikovsky launched a musical exploration of the concept of Fate as an inescapable force. In a letter to Mme. von Meck, Tchaikovsky explained, “The introduction is the seed of the whole symphony, undoubtedly the central theme. This is Fate, i.e., that fateful force which prevents the impulse to happiness from entirely achieving its goal, forever on jealous guard lest peace and well-being should ever be attained in complete and unclouded form, hanging above us like the Sword of Damocles, constantly and unremittingly poisoning the soul. Its force is invisible and can never be overcome. Our only choice is to surrender to it, and to languish fruitlessly.”

The Fate motive blasts open the symphony with a mighty proclamation from the brasses and bassoons. “One’s whole life is just a perpetual traffic between the grimness of reality and one’s fleeting dreams of happiness,” Tchaikovsky wrote of this movement. This theme returns later in the movement and at the end of the fourth, a reminder of destiny’s inescapability.

The beauty of the solo oboe that begins the Andantino beckons, and the yearning countermelody of the strings surges with surprising energy before it subsides. In the Scherzo, Tchaikovsky departs from the heaviness of the previous movements with pizzicato strings. Tchaikovsky described this playful movement as a series of “capricious arabesques.”

As in the first movement, the Finale bursts forth with a blaze of sound. Marked Allegro con fuoco (with fire), the music builds to a raging inferno. Abruptly, Fate returns and the symphony concludes with barely controlled frenzy, accented by cymbal crashes.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com