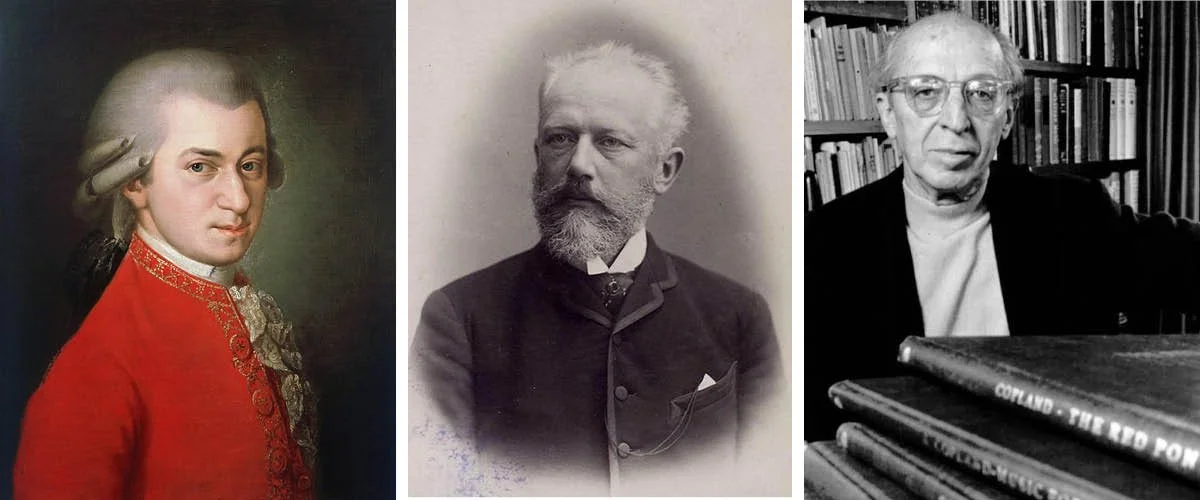

Program Notes: Tchaikovsky & Copland

Notes about:

Mozart’s Overture to The Marriage of Figaro KV492

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23

Copland’s Symphony No. 3

Program Notes for october 13 & 14, 2023

Tchaikovsky & Copland

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Overture from Le nozze di Figaro, K. 492

Composer: born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria; died December 5, 1791, Vienna

Work composed: May 28, 1786.

World premiere: Mozart conducted the first performance of Figaro at Vienna’s Burgtheater on May 1, 1786

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 4 minutes

The best way to generate interest in something is to ban it. This holds as true today as it did in 1782, when King Louis XIV, after attending a private reading of a French comedy of manners written by Pierre Beaumarchais, declared it “detestable.” Beaumarchais’ play contained revolutionary ideas too dangerous for commoners to hear, as far as the rulers of Europe was concerned. Austria’s Emperor Joseph II agreed, and banned Beaumarchais’ play within Austria’s borders.

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart encountered Beaumarchais’ subversive play, he saw in it the perfect basis for an opera. With librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, Mozart relocated the story of Figaro, Susanna, Count Almaviva and Countess Rosina, and all their circle to Italy, and toned down the more obvious revolutionary elements.

The dizzyingly intricate plot of Le nozze di Figaro, Mozart’s most popular and frequently staged opera, is rife with twists, turns, reversals, misunderstandings, rumors, gossip, and deceptions. Such narrative complexity is mirrored in the Overture’s series of running notes, which generate the nonstop high energy needed to keep the story going over four acts. As was common at the time, none of the actual music in the opera appears in the Overture, but the anticipatory excitement of the music readies the audience for all the shenanigans to come.

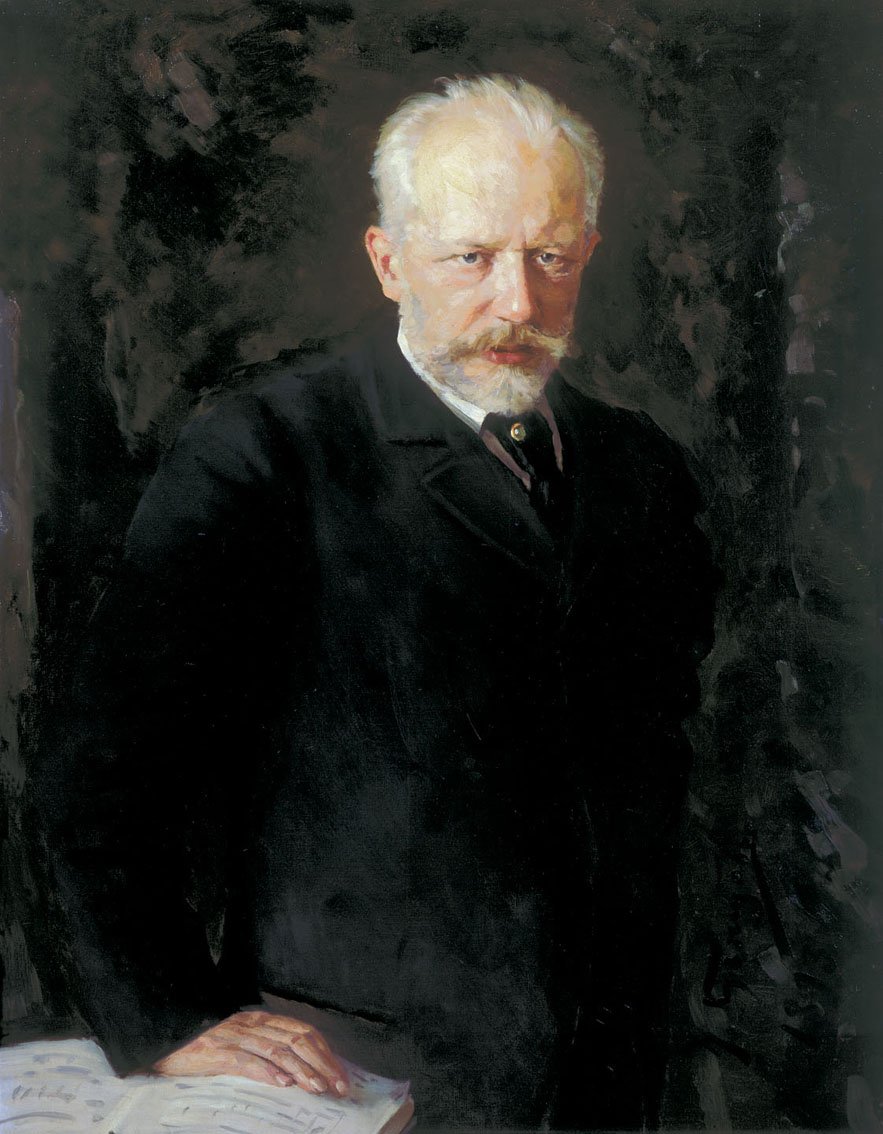

Piotr ilyich tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No.1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23

Composer: born May 7, 1840, Kamsko-Votinsk, Vitaka province, Russia; died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg

Work composed: Tchaikovsky began composing his first piano concerto in November 1874 and finished it in February, 1875. He revised it in the summer of 1879 and again in December 1888; this final revision is the one usually performed. Tchaikovsky originally dedicated the concerto to his mentor Nicolai Rubinstein, but after Rubinstein declared it unplayable, Tchaikovsky removed his mentor’s name from the manuscript and dedicated it to pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow.

World premiere: Valter Poole led the Michigan WPA Symphony Orchestra (aka the Detroit Civic Symphony) on November 6, 1940

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration: 33 minutes

The first measures of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 have assumed an identity all their own. Many people recognize the four-note descending horn theme and the iconic crashing chords of the pianist’s first entrance without knowing the work as a whole. Interestingly, this signature introduction to the Piano Concerto No. 1 is just that, an introduction; after approximately 100 measures it disappears and never returns. These opening bars have also become part of popular culture, as the theme to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre radio programs; in the 1971 cult film Harold and Maude; and in a Monty Python sketch.

Although the rest of the concerto is equally compelling, that was not the initial opinion of Tchaikovsky’s friend and mentor, Nikolai Rubinstein. Rubinstein, director of the Moscow Conservatory, had premiered many of Tchaikovsky’s works, including Romeo and Juliet. Tchaikovsky considered Rubinstein “the greatest pianist in Moscow,” and wanted Rubinstein’s help regarding the technical aspects of the solo piano part. In a letter to his patron Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky described his now-infamous meeting with Rubinstein on Christmas Eve, 1874: “I played the first movement. Not a single word, not a single comment!” After Tchaikovsky finished, as he explained to Mme. von Meck, “A torrent poured from Nikolai Gregorievich’s mouth … My concerto, it turned out, was worthless and unplayable – passages so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written as to be beyond rescue – the music itself was bad, vulgar – only two or three pages were worth preserving – the rest must be thrown out or completely rewritten.”

It is true that this concerto is awkwardly constructed in places, with some abrupt musical transitions. The writing for the soloist is often exceedingly difficult, because Tchaikovsky was not a pianist and did not possess a player’s kinetic, idiomatic knowledge. However, Rubinstein’s excessively negative reaction seems disproportionate.

After the majestic introduction, which anticipates the harmonic language of the following movements, the Andante non troppo continues with a theme Tchaikovsky borrowed from a Ukrainian folk song. Woodwinds introduce a second theme, gentler and quieter, later echoed by the piano. The movement ends with a huge cadenza featuring a display of virtuoso solo fireworks.

In the Andantino semplice, Tchaikovsky also features a borrowed melody, “Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire” (You must enjoy yourself by dancing and laughing) from the French cabaret. Tchaikovsky likely meant this tune as a wistful tribute to the soprano Désirée Artôt, with whom he had been in love a few years previously. (In another musical compliment, Tchaikovsky used the letters of her name as the opening notes of a melody from the first movement).

The galloping melody of the Allegro con fuoco, another Ukrainian folk song, suggests a troika of horses racing over the steppes. A rhapsodic theme in the strings recalls the lush texture of the introduction. The two melodies alternate and overlap, dancing toward a monumental coda.

Aaron Copland

Symphony No. 3

Composer: born November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, NY; died December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, NY

Work composed: 1944-46. Copland’s Third Symphony was commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation and Copland dedicated it “to the memory of my good friend, Natalie Koussevitzky.”

World premiere: Serge Koussevitzky led the Boston Symphony Orchestra on October 18, 1946.

Instrumentation: piccolo, 3 flutes (one doubling 2nd piccolo), 3 oboes (one doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, anvil, bass drum, chimes, claves, cymbals, glockenspiel, ratchet, slapstick, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tam tam, tenor drum, triangle, wood block, xylophone, celeste, piano, 2 harps, and strings.

Estimated duration: 38 minutes

In 1922, Nadia Boulanger, who taught composition to many of the 20th century’s greatest composers, introduced conductor Serge Koussevitzky to one of her young American students. From that moment, Koussevitzky and Aaron Copland forged a reciprocal collaboration that lasted until Koussevitzky’s death, in 1951. Koussevitzky championed Copland’s music and taught him the nuances of conducting; in turn, Copland encouraged Koussevitzky to focus on American composers, particularly at the Berkshire Music Center (now the Tanglewood Music center), which Koussevitzky established in 1940 in Lenox, MA.

In 1944, Copland received his last commission from Koussevitzky’s Foundation; this evolved into his most substantial orchestral work, the Third Symphony. Copland explained, “I knew exactly the kind of music he [Koussevitzky] enjoyed conducting and the sentiments he brought to it, and I knew the sound of his orchestra, so I had every reason to do my darndest to write a symphony in the grand manner.”

In his autobiography, Copland wrote, “If I forced myself, I could invent an ideological basis for the Third Symphony. But if I did, I’d be bluffing – or at any rate, adding something ex post facto, something that might or might not be true but that played no role at the moment of creation.” Nonetheless, one cannot help hearing Copland’s Third Symphony as the expression of a country emerging victorious from a devastating war. Copland acknowledged as much, noting that the Third Symphony “intended to reflect the euphoric spirit of the country at the time.”

Copland described the Molto moderato as “open and expansive.” Of particular note is the second theme, a singing melody for violas and oboes, which sounds like an inspirational moment from a film score.

The Andantino quasi allegretto contains the most abstract and introspective music in the symphony. High strings wander through an empty landscape, like soldiers stumbling upon a field after a bloody battle. A solo flute intones a melody that binds the rest of the movement together with, as Copland explains, “quiet singing nostalgia, then faster and heavier – almost dance-like; then more childlike and naïve, and finally more vigorous and forthright.” As the third movement’s various themes weave and coalesce, sounding much like sections of Copland’s ballet music, they produce a half-conscious sense of déjà vu – have we heard this before? Not quite, but almost, and as the third movement dissolves without pause into the final movement, we hear the woodwinds repeating a theme present in all three of the preceding sections. Now the theme shifts, the last jigsaw puzzle piece locks into place, and the Fanfare for the Common Man emerges.

Although the Fanfare is instantly recognizable today, at the time Copland was writing the Third Symphony it was little known. In 1942, Eugene Goossens, music director of the Cincinnati Symphony, commissioned Copland and eighteen other composers to write short, patriotic fanfares, for the orchestra to premiere during their 1942-43 season. Copland explained his choice of title: “It was the common man, after all, who was doing all the dirty work in the war and the army. He deserved a fanfare.”

Copland wanted a heroic finale to represent the Allied victory in WWII, and the Fanfare epitomized it. The flutes and clarinets introduce the basic theme, before the brasses and percussion burst forth with the version most familiar to audiences.

Reviews were enthusiastic, ranging from Koussevitzky’s categorical statement that it was the finest American symphony ever written to Leonard Bernstein’s declaration, “The Symphony has become an American monument, like the Washington Monument or the Lincoln Memorial.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

Notes about:

Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, op. 62

Wijeratne’s Tabla Concerto

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 in F minor, op. 36

Program Notes for May 6 & 7, 2022

Haas conducts Wijeratne & Tchaikovsky

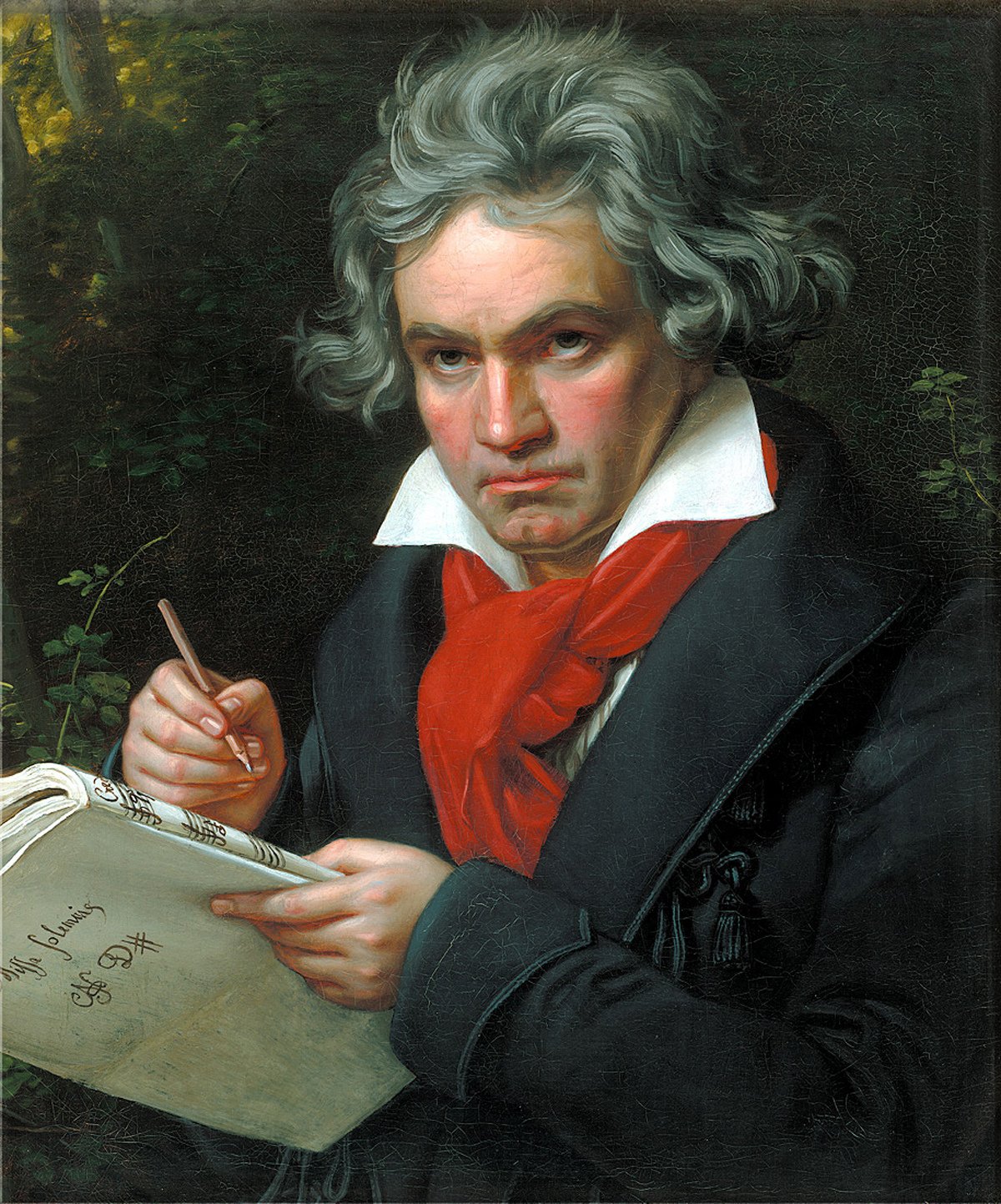

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Coriolan Overture, op. 26

Composer: born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

Work composed: 1807

World premiere: Beethoven conducted a private concert in the Vienna palace of his patron, Prince Lobkowitz, in March 1807, in a performance that also included premieres of his Symphony No. 4 and Piano Concerto No. 4.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Most overtures serve as instrumental introductions to operas or plays. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, although inspired by his countryman Heinrich Joseph Collin’s play about the Roman general Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, was a purely orchestral work from its inception. Unfortunately for Collin, his play, unlike Shakespeare’s on the same subject, was not well received in its initial run in 1804, nor its revival three years later.

In Collin’s play, a hubristic Coriolanus declares war on his hometown of Rome, which had exiled him for his inattention to its plebeian citizens. Enraged, Coriolanus enlists the help of Rome’s most fearsome enemies, the Volsci, to storm the city. As Coriolanus approaches at the head of the Volscian armies, Roman officials sue for peace, to no avail. Coriolanus’ wife, Volumnia, along with his mother and his two sons, also beg him to cease fighting. Coriolanus is moved by his family’s entreaties and, overcome with shame at his dishonorable behavior, literally falls on his sword (this differs from Shakespeare’s ending, in which Coriolanus is murdered).

The dramatic elements of Coriolanus’ story inspired Beethoven’s musical imagination. The music traces an emotional arc, contrasting Coriolanus’ fury and bellicosity with Volumnia’s quiet, forceful pleas for peace.

Dinuk Wijeratne

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born 1978, Sri Lanka

Work composed: 2011, commissioned by Symphony Nova Scotia

World premiere: Recorded live by the CBC, February 9th, 2012 at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium, Halifax, Nova Scotia, featuring Ed Hanley (Tabla) & Symphony Nova Scotia conducted by Bernhard Gueller.

*The Tabla Concerto was twice a finalist for the Masterworks Arts Award (2012, 2016).

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling cor anglais), 2 clarinets in B♭ (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 2 horns in F, 2 trumpets in B, 1 trombone, timpani, 2 percussion, harp, strings

Duration: 27 minutes

Composer’s original program notes:

Canons, Circles

Folk song: ‘White in the moon the long road lies (that leads me from my love)’

Garland of Gems

While the origins of the Tabla are somewhat obscure, it is evident that this ‘king’ of Indian percussion instruments has achieved global popularity for the richness of its timbre, and for the virtuosity of a rhythmically complex repertoire that cannot be separated from the instrument itself. In writing a large-scale work for Tabla and Symphony Orchestra, it is my hope to allow each entity to preserve its own aesthetic. Perhaps, at the same time, the stage will be set for some new discoveries.

While steeped in tradition, the Tabla lends itself heartily to innovation, and has shown its cultural versatility as an increasingly sought-after instrument in contemporary Western contexts such as Pop, Film Music, and World Music Fusion. This notion led me to conceive of an opening movement that would do the not-so-obvious by placing the Tabla first in a decidedly non-Indian context. Here, initiated by a quasi-Baroque canon in four parts, the music quickly turns into an evocation of one my favourite genres of electronic music: ‘Drum-&-Bass’, characterised by rapid ‘breakbeat’ rhythms in the percussion. Of course, there are some North-Indian Classical musical elements present. The whole makes for a rather bizarre stew that reflects globalisation, for better or worse!

A brief second movement becomes a short respite from the energy of the outer movements, and offers a perspective of the Tabla as accompanist in the lyrical world of Indian folk-song. Set in ‘dheepchandhi’, a rhythmic cycle of 14 beats, the gently lilting gait of theTabla rhythm supports various melodic fragments that come together to form an ephemeral love-song.

Typically, a Tabla player concluding a solo recital would do so by presenting a sequence of short, fixed (non-improvised) compositions from his/her repertoire. Each mini-composition, multi-faceted as a little gem, would often be presented first in the form of a vocal recitation. The traditional accompaniment would consist of a drone as well as a looping melody outlining the time cycle – a ‘nagma’ – against which the soloist would weave rhythmically intricate patterns of tension and release. I wanted to offer my own take on a such a recital finale, with the caveat that the orchestra is no bystander. In this movement, it is spurred on by the soloist to share in some of the rhythmic complexity. The whole movement is set in ‘teentaal’, or 16-beat cycle, and in another departure from the traditional norm, my nagma kaleidoscopically changes colour from start to finish. I am indebted to Ed Hanley for helping me choose several ‘gems’ from the Tabla repertoire, although we have certainly had our own fun in tweaking a few, not to mention composing a couple from scratch.

© Dinuk Wijeratne 2011

Notes from the Conductor, Paul Haas:

As a conductor, I’m always on the lookout for great new music. I love that feeling of discovery, especially when I can share it with orchestra musicians and a whole auditorium full of audience members. And Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto is one of the best pieces I’ve ever come across: full of life, emotion, and color.

The first time I ever programmed it (4 years ago in Thunder Bay, Canada) I wanted the Tabla Concerto to end the entire concert, and I needed it to leave the audience ecstatic. There was a stumbling block, though: the third movement (the written ending) of the Tabla Concerto is admittedly wonderful and down-to-earth, and the soloist sings in addition to playing the tablas. But it doesn’t end with that true excitement and momentum I was looking for. From my perspective, it’s almost impossible to end a concert with it, especially if you want the audience so excited they jump out of their seats.

But somehow I knew this was the right piece to close with. So I thought and thought, and eventually it hit me. Dinuk’s Tabla Concerto actually IS the perfect closer, but only if you do the first two movements, and in reverse order. So we started with the second movement, and then we ended with the first movement. And it was sensational. So sensational, in fact, that I begged Dinuk to let me conduct it this way for you, tonight. So that we can end the first half of our evening together with that same feeling of excitement we achieved in Thunder Bay.

Dinuk agreed, and the rest is history. I can’t wait to share his incredible music with you.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No.4 in F minor, Op. 36

Composer: born May 7, 1840, Kamsko-Votinsk, Viatka province, Russia; died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg

Work composed: 1877-78. Dedicated to Nadezhda von Meck

World premiere: Nikolai Rubinstein led the Russian Musical Society orchestra on February 22, 1878, in Moscow

Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 44 minutes

When a former student from the Moscow Conservatory challenged Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky about the “program” for his fourth symphony, the composer responded, “Of course my symphony is programmatic, but this program is such that it cannot be formulated in words. That would excite ridicule and appear comic … In essence, my symphony is an imitation of Beethoven’s Fifth; i.e., I imitated not the musical ideas, but the fundamental concept.”

In December 1876, Tchaikovsky began an epistolary relationship with Mrs. Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and ardent fan of Tchaikovsky’s music. Mme. von Meck offered to become Tchaikovsky’s patron on the condition that they never meet in person; the introverted Tchaikovsky agreed. Soon after von Meck first wrote to Tchaikovsky, he began the Fourth Symphony. As he worked, Tchaikovsky kept von Meck informed of his progress. He dedicated the Fourth Symphony “to my best friend,” which simultaneously paid tribute to von Meck and insured her privacy.

Six months later, Tchaikovsky encountered Antonina Ivanova Milyukova, a former Conservatory student obsessed with her one-time professor. She sent Tchaikovsky several impassioned letters, which alarmed him; eventually Milyukova threatened to kill herself if Tchaikovsky did not return her affection. This untenable situation, combined with Tchaikovsky’s tortured feelings about his sexual orientation and his desire to silence gossip about it, led to a hasty, ill-advised union. Tchaikovsky fled from Milyukova a month after the wedding (their marriage officially ended after three months, although they were never divorced) and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. He was unable to compose any music for the next three years.

Beginning with the Fourth Symphony, Tchaikovsky launched a musical exploration of the concept of Fate as an inescapable force. In a letter to Mme. von Meck, Tchaikovsky explained, “The introduction is the seed of the whole symphony, undoubtedly the central theme. This is Fate, i.e., that fateful force which prevents the impulse to happiness from entirely achieving its goal, forever on jealous guard lest peace and well-being should ever be attained in complete and unclouded form, hanging above us like the Sword of Damocles, constantly and unremittingly poisoning the soul. Its force is invisible and can never be overcome. Our only choice is to surrender to it, and to languish fruitlessly.”

The Fate motive blasts open the symphony with a mighty proclamation from the brasses and bassoons. “One’s whole life is just a perpetual traffic between the grimness of reality and one’s fleeting dreams of happiness,” Tchaikovsky wrote of this movement. This theme returns later in the movement and at the end of the fourth, a reminder of destiny’s inescapability.

The beauty of the solo oboe that begins the Andantino beckons, and the yearning countermelody of the strings surges with surprising energy before it subsides. In the Scherzo, Tchaikovsky departs from the heaviness of the previous movements with pizzicato strings. Tchaikovsky described this playful movement as a series of “capricious arabesques.”

As in the first movement, the Finale bursts forth with a blaze of sound. Marked Allegro con fuoco (with fire), the music builds to a raging inferno. Abruptly, Fate returns and the symphony concludes with barely controlled frenzy, accented by cymbal crashes.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com