Program Notes: The Four Seasons Mixtape

Notes about:

Mendelssohn’s Overture from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Ortiz’s La Calaca for String Orchestra

The Four Seasons Mixtape:

Vivaldi’s L’estate (Summer)

Richter’s Autumn from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver (Wintersong)

Piazzolla’s Primavera portena (Beunos Aires Spring)

Program Notes for November 1 & 2, 2024

The Four Seasons Mixtape

Felix Mendelssohn

Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: 1826

World premiere: Mendelssohn’s first version of the Overture was a two-piano arrangement for himself and his sister Fanny, which they premiered at their home in Berlin on November 19, 1826, for their piano teacher, Ignaz Moscheles. After that performance, Mendelssohn scored the work for orchestra and conducted the first performance of the orchestral version himself the following February in the city of Stettin.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

In July 1826, Felix Mendelssohn began composing what would become one of his most enduring works. Immediately upon its completion, the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream established the 17-year-old Mendelssohn as a composer of depth and astonishing maturity.

Young Felix and his family were ardent fans of Shakespeare, whose works had been translated into German in 1790. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses had read the plays in English and had attempted some translations of his own, including bits from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Felix and his older sister, the equally talented Fanny, immediately took to the fanciful play and staged a series of at-home performances, each child playing multiple roles. In a letter to their sister Rebecka some years after the Overture was composed, Fanny wrote, “Yesterday we were thinking about how the Midsummer Night’s Dream has always been such an inseparable part of our household, how we read all the different roles at various ages, from Peaseblossom to Hermia and Helena … We have really grown up together with the Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Felix, in particular, has made it his own.”

Much more than a simple introduction, Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream serves as the perfect musical description of Shakespeare’s play, which was Mendelssohn’s intention. He thought of the work as a kind of mini-tone poem, rather than a musical prologue to the play itself. In just twelve minutes, Mendelssohn captures the airy magic that imbues the story: the opening chords representing the enchanted forest; the lissome, iridescent violin passages evoking fairies fluttering here and there; the alternately affectionate and turbulent encounters among the four lovers; the dismaying bray of Bottom after he is transformed into a donkey. It is a stunning achievement for a composer of any age.

While he was at work on the Overture, Mendelssohn played violin in an orchestra that performed the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon. In a letter to his father and sister, Mendelssohn sketched out several of its themes, all musical representations of ideas from the opera’s libretto. This experience suggested to Mendelssohn that he intertwine recurring motifs into his own Overture that would, in his words, “weave like delicate threads throughout the whole.”

Gabriela Ortiz

La Calaca for String Orchestra (The Skull)

Composer: born December 20, 1964, Mexico City

Work composed: originally the final movement of Altar de Muertos, a string quartet written for and commissioned by the Kronos Quartet in 1996-97. Arranged for string orchestra in 2021

World premiere: John Adams led the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra at Libbey Bowl in Ojai, CA, on September 19, 2021.

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 10 minutes

Born into a musical family, Gabriela Ortiz has always felt she didn’t choose music – music chose her. Her parents were founding members of the group Los Folkloristas, a renowned music ensemble dedicated to performing Latin American folk music. Growing up in cosmopolitan Mexico City, Ortiz’s music education was multifaceted; she played charango and guitar with Los Folkloristas while also studying classical piano. Later, Ortiz was mentored in composition by renowned Mexican composers Mario Lavista, Julio Estrada, Federico Ibarra, and Daniel Catán. Ortiz continued her studies in Europe, earning a doctorate in composition and electronic music from London’s City University under the guidance of Simon Emmerson.

Ortiz’s music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works. This is, perhaps, the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre: an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds. While Ortiz continues to draw inspiration from Mexican subjects, she is interested in composing music that speaks to international audiences.

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel, a longtime champion of Ortiz’s music, stated: “Gabriela is one of the most talented composers in the world – not only in Mexico, not only in our continent – in the world. Her ability to bring colors, to bring rhythm and harmonies that connect with you is something beautiful, something unique.” Under Dudamel’s direction, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has commissioned and premiered seven works by Ortiz in recent years, including her ballet Revolución diamantina (2023), her violin concerto Altar de Cuerda (2021), and Kauyumari (2021) for orchestra. These three works are featured on the album Revolución diamantina, which was released in June 2024.

La Calaca began as the final movement of Altar de Muertos (Altar of the Dead), a string quartet commissioned by the Kronos Quartet. Altar de Muertos reflects the traditions and festivities of the Day of the Dead. Ortiz writes, “The tradition of the Day of the Dead festivities in Mexico is the source of inspiration for the creation of a work for string quartet whose ideas could reflect the internal search between the real and the magic, a duality always present in Mexican culture, from the past to this present.”

Each movement of Altar embodies the “diverse moods, traditions and the spiritual worlds which shape the global concept of death in Mexico, plus my own personal concept of death,” Ortiz explains. In La Calaca, the music expresses “Syncretism [in religion, the practice of merging beliefs and rituals from disparate traditions] and the concept of death in modern Mexico, chaos and the richness of multiple symbols, where the duality of life is always present: sacred and profane; good and evil; night and day; joy and sorrow. This movement reflects a musical world full of joy, vitality, and a great expressive force. At the end of La Calaca I decided to quote a melody of Huichol origin, which attracted me when I first heard it. That melody was sung by Familia de la Cruz. The Huichol culture lives in the State of Nayarit, Mexico. Their musical art is always found in ceremonial and ritual life.”

The Four Seasons Mixtape

“A mixtape, harkening back to the days of holding a cassette recorder up to the radio, has come into the modern lexicon as a compilation of different musical selections, often from different artists or composers, and usually evoking some similar mood or subject matter,” writes Modesto Symphony Orchestra’s Music Director Nicholas Hersh. “In fact, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is perhaps an early representation of this concept: a set of four violin concerti, each of which can be performed separately, but when taken together they form a greater narrative. Our MSO ‘Four Seasons Mixtape’ takes this a step further by assigning each season to a different composer. Vivaldi’s original Summer sets the tone, and Max Richter’s Autumn [Recomposed] follows it up with a ‘remix’ of the Baroque sound with modern harmony and syncopation. Belgian violin virtuoso Eugene Ysaÿe’s Wintersong imparts a Romantic sumptuousness to an otherwise bleak season, and finally Astor Piazzolla takes us home with his uproarious Buenos Aires Spring, infused with the rhythms of the Tango.

“It is no easy feat to perform such wildly different musical styles as part of the same whole, and I am so grateful to Audrey Wright for realizing this Mixtape with us!”

Antonio Vivaldi

“L’estate” (Summer) from The Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8 No 2

Composer: born March 4, 1678, Venice; died July 27/28, 1741, Vienna

Work composed: published 1725. Dedicated to Count Wenceslas Morzin.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, continuo, and strings

Estimated duration: 11.5 minutes

Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are some of the most recognizable and most performed Baroque works ever written. They have also been used by numerous companies to sell products, from diamonds to high-end cars to computers. With that level of exposure, it is easy to assume we “know” The Four Seasons, but there is more to these concertos than meets the eye, or the ear.

The Four Seasons are part of a larger collection of concertos Vivaldi titled Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention). Each concerto is accompanied by a sonnet, possibly written by Vivaldi himself, which gives specific descriptions of the music as it unfolds.

Summer’s slow introduction evokes a hot, humid summer day: “Under the merciless summer sun languishes man and flock; the pine tree burns … ” Lethargic birdcalls are abruptly interrupted by violent thunderstorms. In the slow movement, the soloist (shepherd) cries out in fear for his flock in the blistering heat. While he laments, the ensemble becomes buzzing flies. The final movement morphs into a tremendous hailstorm that destroys the crops.

Max Richter

“Autumn” from The Four Seasons Recomposed

Composer: born March 22, 1966, Hamelin, Lower Saxony, West Germany

Work composed: 2011-12

World premiere: André de Ridder led the Britten Sinfonietta with violinist Daniel Hope at the Barbican Centre on October 31, 2012, in London.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 8 minutes

Max Richter’s fusion of classical music and electronic technology, as heard in his genre-defining solo albums and numerous scores for film, TV, dance, art, and fashion, has blazed a trail for a generation of musicians.

In 2011, the recording label Deutsche Grammophon invited Richter to join its acclaimed Recomposed series, in which contemporary artists are invited to re-work a traditional piece of music. Richter chose Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. In a 2014 interview with the website Classic FM, Richter explained, “When I was a young child I fell in love with Vivaldi’s original, but over the years, hearing it principally in shopping centres, advertising jingles, on telephone hold systems and similar places, I stopped being able to hear it as music; it had become an irritant – much to my dismay! So I set out to try to find a new way to engage with this wonderful material, by writing through it anew – similarly to how scribes once illuminated manuscripts – and thus rediscovering it for myself. I deliberately didn’t want to give it a modernist imprint but to remain in sympathy and in keeping with Vivaldi’s own musical language.”

“ … The key thing for me to figure out when navigating through this material was just how much Vivaldi and how much me was happening at any point,” Richter continued. “Three quarters of the notes in the new score are mine, but that is not the whole story. Vivaldi’s DNA is omnipresent in the work, and trying to take that into account at all times was the key challenge for me.”

Richter’s version of “Autumn” inserts syncopations (rhythmic off-beats) and subtle electronics into Vivaldi’s original music; the overall effect blurs the boundaries between which phrases are Vivaldi’s and which are Richter’s to a remarkable degree. “I’ve used electronics in several movements, subtle, almost inaudible things to do with the bass,” says Richter, “but I wanted certain moments to connect to the whole electronic universe that is so much part of our musical language today.”

During the recording sessions for Richter’s Recomposed Four Seasons, the composer adds, “In the second movement of ‘Autumn,’ I asked the harpsichordist Raphael Alpermann to play in what is a rather old-fashioned way, very regularly, rather like a ticking clock. That was partly because I didn’t want the harpsichord part to be attention-seeking, but also because that style connects to various pop records from the 1970s where the harpsichord or Clavinet was featured, including various Beach Boys albums and the Beatles’ Abbey Road.”

Eugène Ysaÿe

Chant d’hiver (Winter Song)

Composer: born July 16, 1858, Liège, Belgium; died May 12, 1931, Liège

Work composed: 1902

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 12.5 minutes

Known during his lifetime as “The King of the Violin,” Eugène Ysaÿe was also a noted composer and conductor. Born 18 years after the death of the legendary Italian violinist Niccolò Paganini, the Belgian virtuoso was – and is – widely considered the greatest violinist of his time. This opinion was shared by the foremost composers of the latter 19th – and early 20th-century, including Claude Debussy, Ernest Chausson, Gabriel Faurè, and fellow Belgian César Franck, all of whom dedicated works to Ysaÿe.

Ysaÿe’s Chant d’hiver was inspired by a famous poem from medieval French poet François Villon (c.1431-after 1463). The poem, known in English as “Ballad of the Ladies of Bygone Times,” features a wistful refrain, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” The exquisite melancholy of the soloist’s long phrases and the orchestra’s deft accompaniment evoke an air of longing – and also captures the quintessentially Romantic situation in which one is sad while simultaneously finding an odd pleasure in it.

Astor Piazzolla

“Primavera porteña” from Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires (“Spring” from The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: Piazzolla originally composed the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires for Melenita de oro, a play by his countryman, Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz. The movements were written individually, between the years 1965 -1970, and Piazzolla did not originally intend them to be performed as a single work. The original version of Cuatro estaciones is scored for Piazzolla’s quintet, which consisted of violin, electric guitar, piano, bass, and bandóneon (a large button accordion). Tonight’s arrangement, for solo violin and string orchestra, was created in 1999 by Leonid Desyatnikov for violinist Gidon Kremer.

World premiere: Piazzolla and his quintet played the Cuatro estaciones for the first time at the Teatro Regina in Buenos Aires, on May 19, 1970.

Instrumentation: solo violin and strings

Estimated duration: 5 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla and tango are inseparably linked. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that such categories no longer apply.

In the mid-1950s, Piazzolla went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, one of the 20th century’s most renowned composition teachers. She was unimpressed with the scores he showed her but, after insisting he play her some of his own tangos, she declared, “Astor, this is beautiful. I like it a lot. Here is the true Piazzolla – do not ever leave him.” Piazzolla later called this “the great revelation of my musical life,” and followed Boulanger’s advice. He took tango’s raw passion and fire, with its powerful rhythms and edgy melodies, and made it an essential part of classical repertoire.

The version of the Cuatro estaciones porteñas de Buenos Aires heard on tonight’s program was created in 1999 by Russian composer/arranger Leonid Desyatnikov, at the request of violinist Gidon Kremer. Desyatnikov not only arranged Cuatro estaciones, but also inserted quotes from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons into Piazzolla’s music.

Tango’s musical style requires several string techniques not often heard in classical music: wailing glissandos, sharp pizzicatos that threaten to break strings, bouncing harmonics and, in particular, a harsh, scratchy, distinctly “un-pretty” manner of bowing, sometimes using the wood, rather than the hair, of the bow.

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

Program Notes: Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto

Notes about:

Piazzolla’s Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires)

Farrenc’s Symphony No. 3 in G minor

Bach’s Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue”

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Program Notes for April 12 & 13, 2024

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto

Astor piazzolla

Tangazo (Variations on Buenos Aires)

Composer: born March 11, 1921, Mar del Plata, Argentina; died July 5, 1992, Buenos Aires

Work composed: 1969

World premiere: 1970 in Washington, D.C., by the Ensemble Musical de Buenos Aires

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, cymbals, glockenspiel, guiro, tom-toms, triangle, xylophone, piano, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

“For me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.” – Astor Piazzolla

Astor Piazzolla is inextricably linked with tango. He took a dance from the back rooms of Argentinean brothels and blurred the lines between popular and “art” music to such an extent that, in the case of his music, such categories no longer apply.

Tangazo is a later composition, originally scored for solo bandoneon, piano, and strings. Piazzolla was a master of the bandoneón, a small button accordion of German origin, which originally served as a portable church organ. The distinctive sound of the bandoneón became a fundamental element of Piazzolla’s tangos; its insouciance and melancholy permeate Piazzolla’s music, even in works scored for other instruments.

Tangazo begins in the low strings, which murmur a slow introduction with more than a hint of menace. Harmonically, Tangazo often ranges beyond conventional tango tonalities to explore a modernist palette replete with unexpected detours. After the deliberate legato pace of the introduction, a solo oboe takes off with a skittish tango full of bounce and swagger. Legato interludes featuring pensive horn solos alternate with the agitated tango. Overall, Tangazo conveys restlessness, even as its last notes fade away.

Louise farrenc

Symphony No. 3 in G minor

Composer: born May 31, 1804, Paris; died September 15, 1875, Paris

Work composed: 1847

World premiere: 1849, by the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire in Paris

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 33 minutes

During her lifetime, Louise Farrenc was well known as both a composer and outstanding pianist. Throughout the 19th century, she was also the first and only female professor of music on the faculty of the Paris Conservatory.

Farrenc grew up in a family of artists who encouraged their daughter’s musical interests. Young Louise displayed extraordinary talent at the piano in early childhood, and soon began composing her own music. When she was 15, her parents enrolled her at the Paris Conservatory to continue her composition studies, although she was tutored privately by its faculty because women were not admitted to the Conservatory’s composition program at the time..

At 18, Louise married a flutist, Aristede Farrenc, who later founded a music publishing house. By the 1830s, Farrenc was balancing a busy, multifaceted career as a teacher, composer, and pianist who concertized all over France. As a composer, Farrenc also began expanding her portfolio from solo piano music to larger forms such as symphonies, concert overtures, and a number chamber works, including piano quintets and trios. Farrenc, unlike many female composers whose music was discovered only long after their deaths, was able to hear the public performance of all three of her symphonies – which were well-reviewed – during her lifetime.

The symphonic format evolved from earlier German and Italian genres; by the mid-19th century, symphonies epitomized German style. In fervently nationalist France, particularly in Paris, symphonies and their composers faced aesthetic discrimination from those who deemed the symphony an exclusively German art form. Moreover, the idea of a woman writing symphonic music – in the eyes of some putting herself on par with symphonic greats such as Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, and others – seemed an outrageous provocation.

After a brief Adagio for winds, a graceful Allegro ensues, featuring themes in the strings. This opening movement is full of vigor, artful melodies, and a sense of orchestral mastery. Farrenc follows this confident beginning with a serene Adagio cantabile, featuring a solo clarinet soaring over low winds and brasses, suggesting the intimacy of a woodwind quintet. An agitated Scherzo follows, full of quicksilver flashes of light and shadow that showcases the upper winds. The Finale bristles with dramatic energy and features several powerful statements that unleash the strings’ fiery virtuosity with a series of scalar passages. Minor-key symphonies of this period usually conclude in their corresponding major key, but Farrenc maintains the G-minor intensity right up to the closing notes.

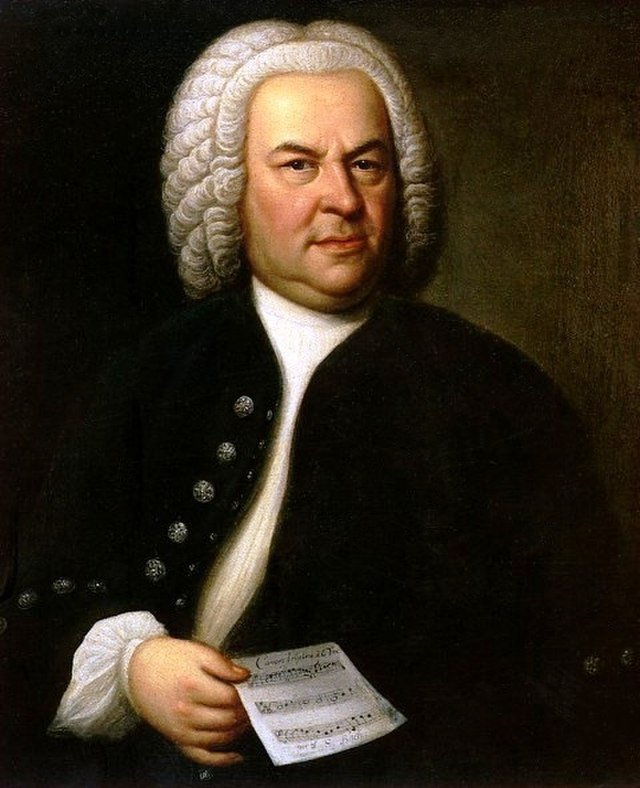

Johann Sebastian Bach

Fugue in G minor BWV 578 “Little Fugue” arr. Hersh

Composer: born March 21, 1685, Eisenach; died July 28, 1750, Leipzig

Work composed: c. 1703-07, written while Bach served as an organist in Arnstadt.

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, chimes, vibraphone, and strings

Estimated duration: 3.5 minutes

Nicknames can be misleading. The only thing “little” about Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue in G minor, BWV 578, is its length. Just under four minutes long, this fugue features one of Bach’s best known and most recognizable fugue subjects, and it has been arranged for diverse ensembles, including Leopold Stowkowsi’s brass-heavy arrangement for full orchestra, and the Swingle Singers’ popular vocal jazz version.

Bach was renowned during his lifetime for his extraordinary ability to improvise at the keyboard. It is possible the distinctive fugue subject emerged first as an improvisation; at over four measures long, it is an unusually lengthy statement. Bach allows each voice to shine, including the basses (played by foot pedals on the organ). The opening three notes cut through the dense counterpoint, announcing the subject’s entrance clearly each time, as the music swirls and eddies towards a bold conclusion.

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Composer: born February 3, 1809, Hamburg; died November 4, 1847, Leipzig

Work composed: July 1838 – September 1844

World premiere: Niels Gade led the Gewandhaus Orchestra and violinist Ferdinand David in Leipzig on March 13, 1845

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 27 minutes

“I would like to write a violin concerto for you next winter,” wrote Felix Mendelssohn to his longtime friend and colleague Ferdinand David in the summer of 1838. “There’s one in E minor in my head, and its opening won’t leave me in peace.” Mendelssohn, then conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, had known David for years. The two prodigies met as teenagers; 15-year-old David was a budding violin virtuoso and 16-year-old Mendelssohn had just completed his Octet for Strings. Years later, when Mendelssohn was appointed director of the Gewandhaus concerts in 1835, he hired David as concertmaster. In 1843, Mendelssohn founded the Leipzig Conservatory and quickly appointed David to the violin faculty.

Mendelssohn had played the violin since childhood, and by all accounts was quite accomplished. However, the E minor Violin Concerto required a level of technical knowledge and skill beyond Mendelssohn’s abilities, so he turned to David for hands-on advice. During the composition of the E minor Concerto, Mendelssohn wrote the melodies and designed the overall structure, while David served as technical consultant.

In this concerto, the violin is always and indisputably the star, while the orchestra’s role provides what the late music critic Michael Steinberg called “accompaniment, punctuation, scaffolding and a bit of cheerleading.” Music this familiar can be difficult to hear as a “composed” work at all; instead, it seems to emerge sui generis, like Athena bursting fully formed from the head of Zeus.

In a break with convention, the solo violin rather than the full orchestra opens the Allegro molto appassionato with the main theme. Mendelssohn also defied expectations by placing the first movement cadenza, which David composed, between the development and return of the main theme, rather than at the end of the movement.

A solo bassoon holds the last note of the Allegro and pivots without interruption to the Andante. Here the soloist leads with a lyrical, singing melody full of tender poignancy. The gentle Andante flows almost without pause into the Allegro molto vivace. The exuberant quicksilver theme of the finale contrasts sharply with the intimate Andante, and demands all the soloist’s technical and artistic skill.

Op. 64 turned out to be Mendelssohn’s last completed orchestral work; he died two years after its premiere. Scholar Thomas Grey observed, “It seems fitting, if fortuitous, that [the Violin Concerto] should combine one of his most serious and personal orchestral movements (the opening Allegro) with a nostalgic return to the world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the finale – the world of Mendelssohn’s ‘enchanted youth’ and the music that, more than any other, epitomizes his contribution to the history of music.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com